Childhood Melanoma Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Patient Information [NCI]

This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

General Information About Childhood Melanoma

Melanoma is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in melanocytes (cells that color the skin).

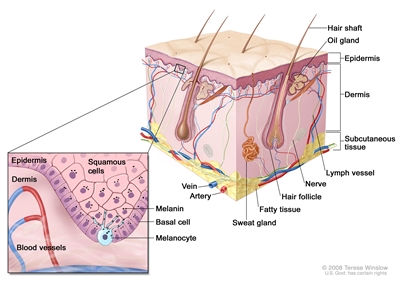

The skin is the body's largest organ. It protects against heat, sunlight, injury, and infection. Skin also helps control body temperature and stores water, fat, and vitamin D. The skin has several layers, but the two main layers are the epidermis (upper or outer layer) and the dermis (lower or inner layer). Skin cancer begins in the epidermis, which is made up of three kinds of cells:

- Squamous cells: Thin, flat cells that form the top layer of the epidermis.

- Basal cells: Round cells under the squamous cells.

- Melanocytes: Cells that make melanin and are found in the lower part of the epidermis. Melanin is the pigment that gives skin its natural color. When skin is exposed to the sun or artificial light, melanocytes make more pigment and cause the skin to darken.

Anatomy of the skin, showing the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. Melanocytes are in the layer of basal cells at the deepest part of the epidermis.

There are different types of cancer that start in the skin.

There are two main forms of skin cancer: melanoma and nonmelanoma (basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin).

Melanoma is a rare form of skin cancer. Even though melanoma is rare, it is the most common skin cancer in children. It occurs more often in adolescents aged 15 to 19 years. Melanoma is more likely to invade nearby tissues and spread to other parts of the body than other types of skin cancer. When melanoma starts in the skin, it is called cutaneous melanoma. Melanoma may also occur in mucous membranes (thin, moist layers of tissue that cover surfaces such as the lips) and the eye (intraocular melanoma). This PDQ summary is about cutaneous (skin) melanoma. (See the PDQ summary on Childhood Intraocular (Uveal) Melanoma Treatment for more information about intraocular melanoma).

Two other types of skin cancer are basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. They rarely spread to other parts of the body. (See the PDQ summary on Childhood Basal Cell Carcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Skin Treatment for more information on basal cell and squamous cell skin cancer.)

Unusual moles, exposure to sunlight, and health history can affect the risk of melanoma.

Anything that increases your risk of getting a disease is called a risk factor. Having a risk factor does not mean that you will get cancer; not having risk factors doesn't mean that you will not get cancer. Talk with your child's doctor if you think your child may be at risk.

Risk factors for childhood melanoma include the following:

- Having one of the following conditions:

- Giant melanocytic nevi (large black spots, which may cover the trunk and thigh).

- Neurocutaneous melanosis (congenital melanocytic nevi in the skin and the brain).

- Xeroderma pigmentosum.

- Hereditary retinoblastoma.

- A weakened immune system.

- Having a fair complexion, which includes the following:

- Fair skin that freckles and burns easily, does not tan, or tans poorly.

- Blue or green or other light-colored eyes.

- Red or blond hair.

Being White or having a fair complexion increases the risk of melanoma, but anyone can have melanoma, including people with dark skin.

- Being exposed to natural sunlight or artificial sunlight (such as from tanning beds).

- Having several large or many small moles.

- Having a family history or personal history of unusual moles (atypical nevus syndrome).

- Having a family history of melanoma.

Signs of melanoma include a change in the way a mole or pigmented area looks.

These and other signs and symptoms may be caused by melanoma or by other conditions.

Check with your child's doctor if your child has any of the following:

- A mole that:

- changes in size, shape, or color.

- has irregular edges or borders.

- is more than one color.

- is asymmetrical (if the mole is divided in half, the 2 halves are different in size or shape).

- itches.

- oozes, bleeds, or is ulcerated (a condition in which the top layer of skin breaks down and the tissue below shows through).

- A change in pigmented (colored) skin.

- Satellite moles (new moles that grow near an existing mole).

Tests that examine the skin are used to diagnose melanoma.

If a mole or pigmented area of the skin changes or looks abnormal, the following tests and procedures can help find and diagnose melanoma:

- Physical exam and health history: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. A history of the patient's health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken.

- Skin exam: A doctor or nurse checks the skin for moles, birthmarks, or other pigmented areas that look abnormal in color, size, shape, or texture.

- Biopsy: A procedure to remove the abnormal tissue and a small amount of normal tissue around it. A pathologist looks at the tissue under a microscope to check for cancer cells. It can be hard to tell the difference between a colored mole and an early melanoma lesion. Patients may want to have the sample of tissue checked by a second pathologist. If the abnormal mole or lesion is cancer, the sample of tissue may also be tested for certain gene changes.

There are four main types of skin biopsies:

- Shave biopsy: A sterile razor blade is used to "shave-off" the abnormal-looking growth.

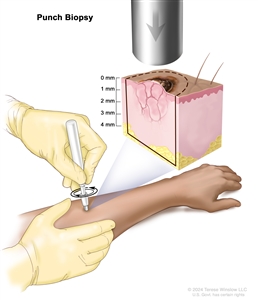

- Punch biopsy: A special instrument called a punch or a trephine is used to remove a circle of tissue from the abnormal-looking growth.

Punch biopsy. A sharp, hollow, circular instrument is used to remove a small, round piece of tissue from a lesion on the skin. The instrument is turned clockwise and counterclockwise to cut about 4 millimeters (mm) down to the layer of fatty tissue below the skin and remove the sample of tissue. Skin thickness is different on different parts of the body. - Incisional biopsy: A scalpel is used to remove part of a growth.

- Excisional biopsy: A scalpel is used to remove the entire growth.

Stages of Melanoma

After melanoma has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer cells have spread to other parts of the body.

The process used to find out if cancer has spread within the skin or to other parts of the body is called staging. There is no standard staging system for childhood melanoma. To plan treatment, it is important to know whether melanoma has spread to lymph nodes or to other parts of the body.

The following procedures may be used to find out if cancer has spread:

- Chest x-ray: An x-ray of the organs and bones inside the chest. An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body.

- CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

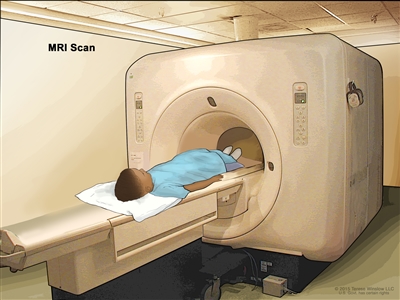

- MRI: A procedure that uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI).

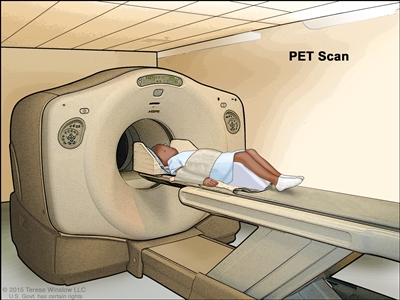

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The child lies on a table that slides into the MRI machine, which takes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. The positioning of the child on the table depends on the part of the body being imaged. - PET scan: A procedure to find malignant tumor cells in the body. A small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) is injected into a vein. The PET scanner rotates around the body and makes a picture of where glucose is being used in the body. Malignant tumor cells show up brighter in the picture because they are more active and take up more glucose than normal cells do.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan. The child lies on a table that slides through the PET scanner. The head rest and white strap help the child lie still. A small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) is injected into the child's vein, and a scanner makes a picture of where the glucose is being used in the body. Cancer cells show up brighter in the picture because they take up more glucose than normal cells do. - Ultrasound: A procedure in which high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) are bounced off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. The picture can be printed to be looked at later.

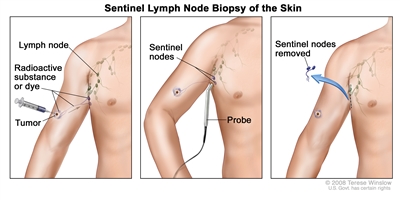

- Sentinel lymph node biopsy: The removal of the sentinel lymph node during surgery. The sentinel lymph node is the first lymph node in a group of lymph nodes to receive lymphatic drainage from the primary tumor. It is the first lymph node the cancer is likely to spread to from the primary tumor. A radioactive substance and/or blue dye is injected near the tumor. The substance or dye flows through the lymph ducts to the lymph nodes. The first lymph node to receive the substance or dye is removed. A pathologist views the tissue under a microscope to look for cancer cells. If cancer cells are not found, it may not be necessary to remove more lymph nodes. Sometimes, a sentinel lymph node is found in more than one group of nodes.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy of the skin. A radioactive substance and/or blue dye is injected near the tumor (first panel). The injected material is detected visually and/or with a probe that detects radioactivity (middle panel). The sentinel nodes (the first lymph nodes to take up the material) are removed and checked for cancer cells (last panel). - Lymph node dissection: A surgical procedure in which lymph nodes are removed and a sample of tissue is checked under a microscope for signs of cancer. For a regional lymph node dissection, some of the lymph nodes in the tumor area are removed. For a radical lymph node dissection, most or all of the lymph nodes in the tumor area are removed. This procedure is also called a lymphadenectomy.

There are three ways cancer spreads in the body.

Cancer can spread through tissue, the lymph system, and the blood:

- Tissue. The cancer spreads from where it began by growing into nearby areas.

- Lymph system. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the lymph system. The cancer travels through the lymph vessels to other parts of the body.

- Blood. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the blood. The cancer travels through the blood vessels to other parts of the body.

Cancer may spread from where it began to other parts of the body.

When cancer spreads to another part of the body, it is called metastasis. Cancer cells break away from where they began (the primary tumor) and travel through the lymph system or blood.

- Lymph system. The cancer gets into the lymph system, travels through the lymph vessels, and forms a tumor (metastatic tumor) in another part of the body.

- Blood. The cancer gets into the blood, travels through the blood vessels, and forms a tumor (metastatic tumor) in another part of the body.

The metastatic tumor is the same type of cancer as the primary tumor. For example, if melanoma spreads to the lung, the cancer cells in the lung are actually melanoma cells. The disease is metastatic melanoma, not lung cancer.

Sometimes childhood melanoma recurs (comes back) after treatment.

The cancer may come back in the skin, lymph nodes, or in other parts of the body.

Treatment Option Overview

There are different types of treatment for children with melanoma.

Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being tested in clinical trials. A treatment clinical trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials show that a new treatment is better than the standard treatment, the new treatment may become the standard treatment.

Because cancer in children is rare, taking part in a clinical trial should be considered. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Children with melanoma should have their treatment planned by a team of doctors who are experts in treating childhood cancer.

Treatment will be overseen by a pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer. The pediatric oncologist works with other pediatric health professionals who are experts in treating children with cancer and who specialize in certain areas of medicine. This may include the following specialists and others:

- Pediatrician.

- Dermatologist.

- Pediatric surgeon.

- Pathologist.

- Social worker.

- Rehabilitation specialist.

- Psychologist.

- Child-life specialist.

Three types of standard treatment are used:

Surgery

Surgery to remove the tumor is used to treat childhood melanoma. A wide local excision is used to remove the melanoma and some of the normal tissue around it. Skin grafting (taking skin from another part of the body to replace the skin that is removed) may be done to cover the wound caused by surgery. Nearby lymph nodes with cancer may also be removed.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a treatment that uses the patient's immune system to fight cancer. Substances made by the body or made in a laboratory are used to boost, direct, or restore the body's natural defenses against cancer. This type of cancer treatment is also called biotherapy or biologic therapy.

- Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: immune checkpoint inhibitorsImmunotherapy uses the body's immune system to fight cancer. This animation explains one type of immunotherapy that uses immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat cancer.

There are different types of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy:

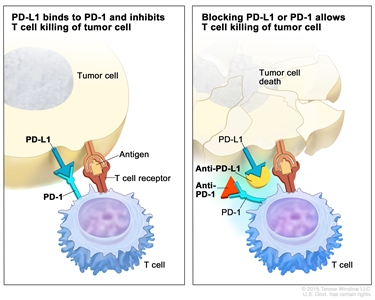

- PD-1 inhibitor: PD-1 is a protein on the surface of T cells that helps keep the body's immune responses in check. When PD-1 attaches to another protein called PDL-1 on a tumor cell, it stops the T cell from killing the tumor cell. PD-1 inhibitors attach to PDL-1 and allow the T cells to kill tumor cells. Pembrolizumab and nivolumab are used to treat melanoma that has spread to lymph nodes and are being studied to treat recurrent melanoma.

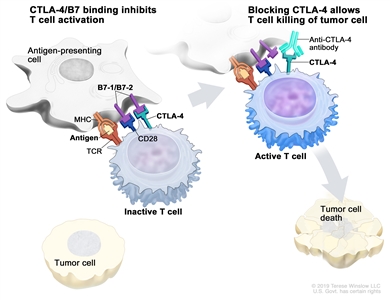

Immune checkpoint inhibitor. Checkpoint proteins, such as PD-L1 on tumor cells and PD-1 on T cells, help keep immune responses in check. The binding of PD-L1 to PD-1 keeps T cells from killing tumor cells in the body (left panel). Blocking the binding of PD-L1 to PD-1 with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (anti-PD-L1 or anti-PD-1) allows the T cells to kill tumor cells (right panel). - CTLA-4 inhibitor: CTLA-4 is a protein on the surface of T cells that helps keep the body's immune responses in check. When CTLA-4 attaches to another protein called B7 on a cancer cell, it stops the T cell from killing the cancer cell. CTLA-4 inhibitors attach to CTLA-4 and allow the T cells to kill cancer cells. Ipilimumab is used to treat melanoma that has spread to lymph nodes or to other parts of the body and is being studied to treat recurrent melanoma.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor. Checkpoint proteins, such as B7-1/B7-2 on antigen-presenting cells (APC) and CTLA-4 on T cells, help keep the body's immune responses in check. When the T-cell receptor (TCR) binds to antigen and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins on the APC and CD28 binds to B7-1/B7-2 on the APC, the T cell can be activated. However, the binding of B7-1/B7-2 to CTLA-4 keeps the T cells in the inactive state so they are not able to kill tumor cells in the body (left panel). Blocking the binding of B7-1/B7-2 to CTLA-4 with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (anti-CTLA-4 antibody) allows the T cells to be active and to kill tumor cells (right panel).

- PD-1 inhibitor: PD-1 is a protein on the surface of T cells that helps keep the body's immune responses in check. When PD-1 attaches to another protein called PDL-1 on a tumor cell, it stops the T cell from killing the tumor cell. PD-1 inhibitors attach to PDL-1 and allow the T cells to kill tumor cells. Pembrolizumab and nivolumab are used to treat melanoma that has spread to lymph nodes and are being studied to treat recurrent melanoma.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a type of treatment that uses drugs or other substances to attack cancer cells. Targeted therapies usually cause less harm to normal cells than chemotherapy or radiation therapy do. The following type of targeted therapy is being used or studied in the treatment of melanoma:

- Signal transduction inhibitor therapy: Signal transduction inhibitors block signals that are passed from one molecule to another inside a cell. Blocking these signals may kill cancer cells. They are used to treat some patients with advanced melanoma or tumors that cannot be removed by surgery. Signal transduction inhibitors include the following:

- BRAF inhibitors (dabrafenib, vemurafenib , or encorafenib) that block the activity of proteins made by mutant BRAF genes.

- MEK inhibitors (trametinib or binimetinib) that block proteins called MEK1 and MEK2 which affect the growth and survival of cancer cells.

New types of treatment are being tested in clinical trials.

Information about clinical trials is available from the NCI website.

Treatment for childhood melanoma may cause side effects.

To learn more about side effects that begin during treatment for cancer, visit Side Effects.

Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial.

For some patients, taking part in a clinical trial may be the best treatment choice. Clinical trials are part of the cancer research process. Clinical trials are done to find out if new cancer treatments are safe and effective or better than the standard treatment.

Many of today's standard treatments for cancer are based on earlier clinical trials. Patients who take part in a clinical trial may receive the standard treatment or be among the first to receive a new treatment.

Patients who take part in clinical trials also help improve the way cancer will be treated in the future. Even when clinical trials do not lead to effective new treatments, they often answer important questions and help move research forward.

Patients can enter clinical trials before, during, or after starting their cancer treatment.

Some clinical trials only include patients who have not yet received treatment. Other trials test treatments for patients whose cancer has not gotten better. There are also clinical trials that test new ways to stop cancer from recurring (coming back) or reduce the side effects of cancer treatment.

Clinical trials are taking place in many parts of the country. Information about clinical trials supported by NCI can be found on NCI's clinical trials search webpage. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Follow-up tests may be needed.

As your child goes through treatment, they will have follow-up tests or check-ups. Some tests that were done to diagnose or stage the cancer may be repeated to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Some of the tests will continue to be done from time to time after treatment has ended. The results of these tests can show if your child's condition has changed or if the cancer has recurred (come back).

Treatment of Childhood Melanoma

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment of newly diagnosed melanoma that has not spread to lymph nodes or other parts of the body includes the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor and some healthy tissue around it.

Treatment of newly diagnosed melanoma that has spread to nearby lymph nodes includes the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor and the lymph nodes with cancer.

- Immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (pembrolizumab, ipilimumab, or nivolumab).

- Targeted therapy with BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib, or encorafenib) alone or with MEK inhibitors (trametinib or binimetinib).

Treatment of newly diagnosed melanoma that has spread to other parts of the body may include the following:

- Immunotherapy (ipilimumab).

- A clinical trial of an oral targeted therapy drug (dabrafenib) in children and adolescents.

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. General information about clinical trials is also available.

Treatment of Recurrent Childhood Melanoma

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment of recurrent melanoma in children may include the following:

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient's tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

- A clinical trial of immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, or ipilimumab) in children and adolescents.

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. General information about clinical trials is also available.

To Learn More About Childhood Melanoma

For more information from the National Cancer Institute about melanoma, see the following:

- Skin Cancer (Including Melanoma) Home Page

- Skin Cancer Prevention

- Skin Cancer Screening

- Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy

- Immunotherapy to Treat Cancer

- Targeted Cancer Therapies

- Moles to Melanoma: Recognizing the ABCDE Features

For more childhood cancer information and other general cancer resources, visit:

- About Cancer

- Childhood Cancers

- CureSearch for Children's Cancer

- Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer

- Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer

- Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents

- Cancer in Children and Adolescents

- Cancer Staging

- Coping with Cancer

- Questions to Ask Your Doctor about Cancer

- For Survivors, Caregivers, and Advocates

About This PDQ Summary

About PDQ

Physician Data Query (PDQ) is the National Cancer Institute's (NCI's) comprehensive cancer information database. The PDQ database contains summaries of the latest published information on cancer prevention, detection, genetics, treatment, supportive care, and complementary and alternative medicine. Most summaries come in two versions. The health professional versions have detailed information written in technical language. The patient versions are written in easy-to-understand, nontechnical language. Both versions have cancer information that is accurate and up to date and most versions are also available in Spanish.

PDQ is a service of the NCI. The NCI is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH is the federal government's center of biomedical research. The PDQ summaries are based on an independent review of the medical literature. They are not policy statements of the NCI or the NIH.

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary has current information about the treatment of childhood melanoma. It is meant to inform and help patients, families, and caregivers. It does not give formal guidelines or recommendations for making decisions about health care.

Reviewers and Updates

Editorial Boards write the PDQ cancer information summaries and keep them up to date. These Boards are made up of experts in cancer treatment and other specialties related to cancer. The summaries are reviewed regularly and changes are made when there is new information. The date on each summary ("Updated") is the date of the most recent change.

The information in this patient summary was taken from the health professional version, which is reviewed regularly and updated as needed, by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board.

Clinical Trial Information

A clinical trial is a study to answer a scientific question, such as whether one treatment is better than another. Trials are based on past studies and what has been learned in the laboratory. Each trial answers certain scientific questions in order to find new and better ways to help cancer patients. During treatment clinical trials, information is collected about the effects of a new treatment and how well it works. If a clinical trial shows that a new treatment is better than one currently being used, the new treatment may become "standard." Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Clinical trials can be found online at NCI's website. For more information, call the Cancer Information Service (CIS), NCI's contact center, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. The content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text. It cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless the whole summary is shown and it is updated regularly. However, a user would be allowed to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks in the following way: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The best way to cite this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Childhood Melanoma Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/skin/patient/child-melanoma-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>.

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use in the PDQ summaries only. If you want to use an image from a PDQ summary and you are not using the whole summary, you must get permission from the owner. It cannot be given by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the images in this summary, along with many other images related to cancer can be found in Visuals Online. Visuals Online is a collection of more than 3,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used to make decisions about insurance reimbursement. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website's E-mail Us.

Last Revised: 2021-10-18

If you want to know more about cancer and how it is treated, or if you wish to know about clinical trials for your type of cancer, you can call the NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-422-6237, toll free. A trained information specialist can talk with you and answer your questions.