Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (PDQ®): Treatment - Patient Information [NCI]

This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

What is childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia?

Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (also called ALL or acute lymphocytic leukemia) is a cancer of the blood and bone marrow. This is the most common type of cancer in children. It accounts for about 25% of all childhood cancers in the United States and occurs most often in children aged 1 to 4 years.

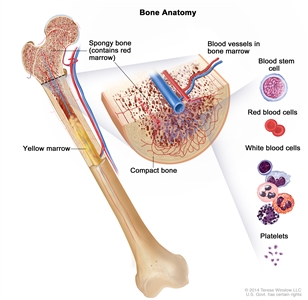

Anatomy of the bone. The bone is made up of compact bone, spongy bone, and bone marrow. Compact bone makes up the outer layer of the bone. Spongy bone is found mostly at the ends of bones and contains red marrow. Bone marrow is found in the center of most bones and has many blood vessels. There are two types of bone marrow: red and yellow. Red marrow contains blood stem cells that can become red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets. Yellow marrow is made mostly of fat.

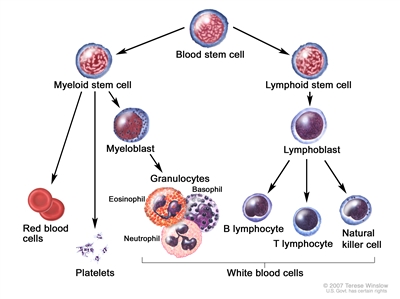

The bone marrow makes blood stem cells (immature cells) that become mature blood cells over time. A blood stem cell may become a myeloid stem cell or a lymphoid stem cell.

A myeloid stem cell becomes one of three types of blood cells:

- red blood cells that carry oxygen and other substances to all the tissues in the body

- granulocytes and other types of white blood cells that help the body's immune system respond to infection, allergens, and inflammation

- platelets that help stop bleeding by forming clots

A lymphoid stem cell becomes a lymphoblast cell and then one of three types of lymphocytes (white blood cells):

- B lymphocytes, which make antibodies to help fight infection

- T lymphocytes, which help B lymphocytes make the antibodies that help fight infection

- natural killer cells, which attack cancer cells and viruses

Blood cell development. A blood stem cell goes through several steps to become a red blood cell, platelet, or white blood cell.

ALL occurs because too many stem cells become lymphoblasts that do not mature into B lymphocytes or T lymphocytes. These cells are also called leukemia cells. Leukemia cells are not able to fight infection very well. Also, as the number of leukemia cells increases in the blood and bone marrow, there is less room for healthy red blood cells, platelets, and white blood cells. This may lead to anemia, easy bleeding, and infection.

ALL usually worsens quickly if it is not treated.

Causes and risk factors for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Childhood ALL is caused by changes to how the blood stem cells function, especially how they grow and divide into new cells. The exact cause of these cell changes is often unknown. Learn more about how cancer develops at What Is Cancer?

A risk factor is anything that increases the chance of getting a disease. Not every child with one or more of these risk factors will develop ALL. And it will develop in some children who don't have a known risk factor. Risk factors may be genetic or due to other causes.

Possible genetic risk factors for ALL include:

- Down syndrome

- neurofibromatosis type 1

- Bloom syndrome

- Fanconi anemia

- ataxia-telangiectasia

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome (TP53 gene)

- constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (mutations in certain genes that stop DNA from repairing itself, which leads to the growth of cancers at an early age)

- having certain changes in chromosomes or genes

Other possible risk factors for ALL include:

- being exposed to x-rays before birth

- being exposed to radiation

- past treatment with chemotherapy

Talk with your child's doctor if you think your child may be at risk.

Genetic counseling for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

It is not always clear from the family medical history whether a child with ALL has an inherited condition that increased their risk. Genetic counseling can assess the likelihood that your child's cancer is inherited and whether genetic testing is needed. Genetic counselors and other specially trained health professionals can discuss your child's diagnosis and family medical history to help you understand:

- the options for testing for changes in the TP53 gene or other genes

- the risk of other cancers for your child

- the risk of ALL and other cancers for your child's siblings

- the risks and benefits of learning genetic information

Genetic counselors can also help you cope with your child's genetic test results, including how to discuss the results with family members. They can advise you about whether other members of your family should receive genetic testing.

Learn more about Genetic Testing for Inherited Cancer Risk.

Symptoms of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Symptoms of childhood ALL are caused by not having enough red blood cells and platelets and by having too many white blood cells that don't work well. It's important to check with your child's doctor if your child has:

- fever

- easy bruising or bleeding

- flat, pinpoint, dark-red spots under the skin caused by bleeding (petechiae)

- weakness or fatigue

- pale skin or looks pale

- bone or joint pain

- shortness of breath or trouble breathing

- painless lumps (swollen lymph nodes) in the neck, underarm, stomach, or groin

- pain or a feeling of fullness below the ribs

- loss of appetite

- weight loss

- abdominal pain

- frequent infections or infections that do not go away

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than ALL. The only way to know is for your child to see a doctor.

Tests to diagnose childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

If your child has symptoms that suggest ALL, the doctor will need to find out if these are due to cancer or another problem. The doctor will ask when the symptoms started and how often your child has been having them. They will also ask about your child's personal and family medical history and do a physical exam. Depending on these results, they may recommend other diagnostic tests. If your child is diagnosed with ALL, the results of these tests will help plan treatment.

The tests used to diagnose childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia may include:

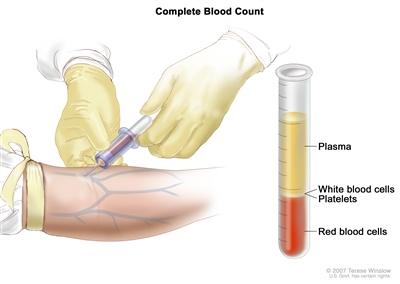

Complete blood count (CBC)

A CBC checks a sample of blood for:

- the number of red blood cells and platelets

- the number and type of white blood cells

- the amount of hemoglobin (the protein that carries oxygen) in the red blood cells

- the amount of hematocrit (whole blood that is made up of red blood cells)

Complete blood count (CBC). Blood is collected by inserting a needle into a vein and allowing the blood to flow into a tube. The blood sample is sent to the laboratory and the red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets are counted. The CBC is used to test for, diagnose, and monitor many different conditions.

Blood chemistry study

Blood chemistry study uses a blood sample to measure the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by organs and tissues in the body. An unusual amount of a substance can be a sign of disease.

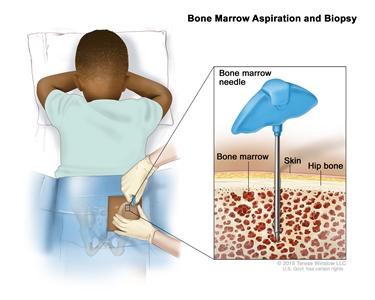

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy

The removal of bone marrow and a small piece of bone by inserting a hollow needle into the hipbone or breastbone. A pathologist views the bone marrow and bone under a microscope to look for cancer.

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. After a small area of skin is numbed, a bone marrow needle is inserted into the child's hip bone. Samples of blood, bone, and bone marrow are removed for examination under a microscope.

Tests done on blood or the bone marrow tissue that is removed include:

- Genetic tests: Many leukemia cells have abnormalities in their genes which can be found by different types of genetic tests. An example of a genetic test that is commonly used is cytogenetic analysis, in which the chromosomes in a sample of blood or bone marrow are counted and checked for any changes, such as broken, missing, rearranged, or extra chromosomes. Genetic testing of blood and bone marrow samples is used to help diagnose cancer, plan treatment, or find out how well treatment is working.

- Immunophenotyping: A laboratory test that uses antibodies to identify cancer cells based on the types of antigens or markers on the surface of the cells. This test is used to help diagnose specific types of leukemia. For example, the cancer cells are checked to see if they are B lymphocytes or T lymphocytes.

Lumbar puncture

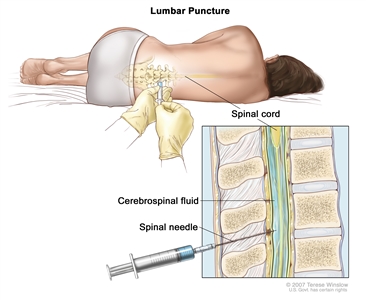

Lumbar puncture is a procedure used to collect a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the spinal column (also called spine) to check for leukemia cells. This is done by placing a needle between two bones in the spine and into the lining around the spinal cord to remove a sample of CSF. The sample of CSF is checked under a microscope for signs that leukemia cells have spread to the brain and spinal cord. This procedure is also called an LP or spinal tap.

Lumbar puncture. A patient lies in a curled position on a table. After a small area on the lower back is numbed, a spinal needle (a long, thin needle) is inserted into the lower part of the spinal column to remove cerebrospinal fluid (CSF, shown in blue). The fluid may be sent to a laboratory for testing.

This procedure is done after leukemia is diagnosed to find out if leukemia cells have spread to the brain and spinal cord. Intrathecal chemotherapy is given after the sample of fluid is removed to treat any leukemia cells that may have spread to the brain and spinal cord.

Chest x-ray

Chest x-ray is a type of radiation that can go through the body and make pictures of the organs and bones inside the chest. The chest x-ray is done to see if leukemia cells have formed a lump in the middle of the chest.

Getting a second opinion

You may want to get a second opinion to confirm your child's cancer diagnosis and treatment plan. If you seek a second opinion, you will need to get medical test results and reports from the first doctor to share with the second doctor. The second doctor will review the genetic test results, pathology report, slides, and scans. This doctor may agree with the first doctor, suggest changes to the treatment plan, or provide more information about your child's tumor.

To learn more about choosing a doctor and getting a second opinion, visit Finding Cancer Care. You can contact NCI's Cancer Information Service via chat, email, or phone (both in English and Spanish) for help finding a doctor or hospital that can provide a second opinion. For questions you may want to ask at your child's appointments, visit Questions to Ask Your Doctor About Cancer.

Risk groups for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

In childhood ALL, risk groups are used to plan treatment. The three risk groups in childhood ALL include:

- Standard risk: Children aged 1 to younger than 10 years who have a white blood cell count less than 50,000 per microliter of blood at the time of diagnosis.

- High risk: Children 10 years and older and/or children who have a white blood cell count of 50,000 per microliter of blood or more at the time of diagnosis.

- Very high risk: Children younger than age 1, children with certain changes in the genes, children who have a slow improvement from initial treatment, and children who have signs of leukemia after the first 4 weeks of treatment.

Other factors that affect the risk group include:

- whether the leukemia cells began from B lymphocytes or T lymphocytes

- whether there are certain changes in the chromosomes or genes of the lymphocytes

- whether the leukemia cell count drops quickly and how low it drops after initial treatment

- whether leukemia cells are found in the cerebrospinal fluid or the testes at the time of diagnosis

- having Down syndrome

- receiving steroids before cancer treatment

It is important to know the risk group in order to plan treatment. Children with high-risk or very high-risk ALL usually receive more anticancer drugs and/or higher doses of anticancer drugs than children with standard-risk ALL.

Types of treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Who treats children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia?

A pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer, oversees treatment of ALL. The pediatric oncologist works with other pediatric health care providers who are experts in treating children with leukemia and who specialize in certain areas of medicine. Other specialists may include:

- pediatrician

- hematologist

- medical oncologist

- pediatric surgeon

- radiation oncologist

- pediatric intensivist

- neurologist

- neuroradiologist

- pediatric nurse specialist

- social worker

- rehabilitation specialist

- psychologist

- child-life specialist

- fertility specialist

Treatment phases of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

The treatment of childhood ALL is done in three phases:

- Remission induction is the first phase of treatment. The goal is to kill the leukemia cells in the blood and bone marrow. This puts the leukemia into remission.

- Consolidation/intensification is the second phase of treatment. It begins once the leukemia is in remission. The goal of consolidation/intensification therapy is to kill any leukemia cells that remain in the body and may cause a relapse.

- Maintenance is the third phase of treatment. The goal is to kill any remaining leukemia cells that may regrow and cause a relapse. Often the cancer treatments are given in lower doses than those used during the remission induction and consolidation/intensification phases. This is also called the continuation therapy phase.

Taking medicine as ordered by the doctor during maintenance therapy decreases the chance the cancer will come back.

Treatment options depend on:

- whether the leukemia cells began from B lymphocytes or T lymphocytes

- if your child has standard-risk, high-risk, or very high-risk ALL

- your child's age at the time of diagnosis

- whether there are certain changes in the chromosomes of lymphocytes, such as the Philadelphia chromosome

- whether your child was treated with dexamethasone or prednisone before the start of remission induction therapy

- how quickly and how low the leukemia cell count drops during treatment

- if leukemia was found in the central nervous system

Types of treatment your child might have include:

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (also called chemo) uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells. Chemotherapy either kills the cells or stops them from dividing. Chemotherapy may be given alone or with other types of treatment.

For ALL, chemotherapy may be given a few ways. Chemotherapy that is taken by mouth or injected into a vein enters the bloodstream and reaches cancer cells throughout the body. Chemotherapy that is placed directly into the cerebrospinal fluid (intrathecal chemotherapy) mainly affects cancer cells in this area.

The way the chemotherapy is given depends on your child's risk group. Children with high-risk ALL receive more anticancer drugs and higher doses of anticancer drugs than children with standard-risk ALL. Intrathecal chemotherapy is used to treat childhood ALL that has spread, or may spread, to the brain and spinal cord.

Chemotherapy drugs used alone or in combination to treat ALL in children include:

- asparaginase

- cyclophosphamide

- cytarabine

- daunorubicin

- dexamethasone (steroid)

- doxorubicin

- etoposide

- mercaptopurine

- methotrexate

- nelarabine

- prednisone (steroid)

- thioguanine

- vincristine

Other drugs not listed here may also be used.

Learn more about how chemotherapy works, how it is given, common side effects, and more at Chemotherapy to Treat Cancer.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. Childhood ALL is treated with external beam radiation therapy. This type of therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the area of the body with cancer. Radiation therapy may be given alone or with other treatments.

External radiation therapy may be used to treat childhood ALL that has spread, or may spread, to the brain, spinal cord, or testicles. It may also be used to prepare the bone marrow for a stem cell transplant.

Learn more about External Beam Radiation Therapy for Cancer and Radiation Therapy Side Effects.

Stem cell transplant

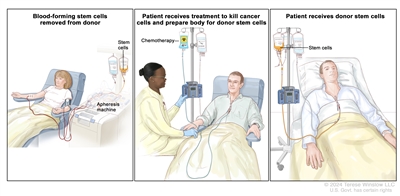

High doses of chemotherapy are given to kill cancer cells. Total-body irradiation is usually given with chemotherapy, but it is sometimes not given to infants and very young children. These treatments destroy healthy cells, including blood-forming cells. Stem cell transplant is a treatment to replace the blood-forming cells. Stem cells (immature blood cells) are removed from the blood or bone marrow of a donor and are frozen and stored. After the patient completes chemotherapy and radiation therapy, the stored stem cells are thawed and given to the patient through an infusion. These stem cells grow into (and restore) the body's blood cells. The donor stem cells may also find and kill any cancer cells left in the body.

Stem cell transplant is rarely used as initial treatment for children and adolescents with ALL. It is used more often as part of treatment for ALL that relapses (comes back after treatment).

Stem cell transplant. (Step 1): Blood is taken from a vein in the arm of the donor. The blood flows through a machine that removes the stem cells. Then the blood is returned to the donor through a vein in the other arm. (Step 2): The patient receives chemotherapy to kill blood-forming cells. The patient may receive radiation therapy (not shown). (Step 3): The patient receives stem cells through a catheter placed into a blood vessel in the chest.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a treatment that uses the patient's immune system to fight cancer. Substances made by the body or made in a laboratory are used to boost, direct, or restore the body's natural defenses against cancer. Examples of immunotherapy used to treat childhood ALL include blinatumomab, rituximab, and CAR T-cell therapy.

- Blinatumomab: Blinatumomab works by bringing healthy T cells (immune cells that help kill cancer cells) and leukemia cells close together so the T cells can more effectively kill the leukemia. It does this by binding to a protein called CD3 on healthy T cells and a protein called CD19 on B cells (the immune cells that are cancerous in acute lymphoblastic leukemia). Blinatumomab is a type of targeted therapy drug called a bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE).

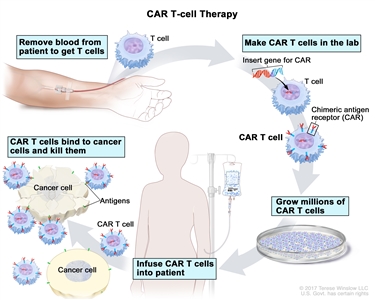

- CAR T-cell therapy: This treatment changes the patient's T-cells (a type of immune system cell) so they will attack certain proteins on the surface of cancer cells. T cells are taken from the patient and special receptors are added to their surface in the laboratory. The changed cells are called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. The CAR T cells are grown in the laboratory and given to the patient by infusion. The CAR T cells multiply in the patient's blood and attack cancer cells. CAR T-cell therapy is being studied in the treatment of childhood ALL that has relapsed (come back) a second time.

CAR T-cell therapy. A type of treatment in which a patient's T cells (a type of immune cell) are changed in the laboratory so they will bind to cancer cells and kill them. Blood from a vein in the patient's arm flows through a tube to an apheresis machine (not shown), which removes the white blood cells, including the T cells, and sends the rest of the blood back to the patient. Then, the gene for a special receptor called a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) is inserted into the T cells in the laboratory. Millions of the CAR T cells are grown in the laboratory and then given to the patient by infusion. The CAR T cells are able to bind to an antigen on the cancer cells and kill them. - Rituximab.

Learn more about Immunotherapy to Treat Cancer.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy uses drugs or other substances to block the action of specific enzymes, proteins, or other molecules involved in the growth and spread of cancer cells. Often, targeted therapies are only used in specific ALL subtypes in which the specific target of the drug is present. Targeted therapy used or studied to treat childhood ALL includes:

- bortezomib

- dasatinib

- imatinib mesylate

- inotuzumab ozogamicin

- nivolumab

- ruxolitinib

Learn more about Targeted Therapy to Treat Cancer.

Clinical trials

For some children, joining a clinical trial may be an option. There are different types of clinical trials for childhood cancer. For example, a treatment trial tests new treatments or new ways of using current treatments. Supportive care and palliative care trials look at ways to improve quality of life, especially for those who have side effects from cancer and its treatment.

You can use the clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials accepting participants. The search allows you to filter trials based on the type of cancer, your child's age, and where the trials are being done. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Learn more about clinical trials, including how to find and join one, at Clinical Trials Information for Patients and Caregivers.

Treatment options for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

There are different types of treatment for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). You and your child's care team will work together to decide treatment. Many factors will be considered, such as your child's age and overall health, and whether the tumor is newly diagnosed or has come back.

Your child's treatment plan will include information about the cancer, the goals of treatment, treatment options, and the possible side effects. It will be helpful to talk with your child's care team before treatment begins about what to expect. For help every step of the way, visit our booklet, Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents.

Treatment of standard-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Treatment of newly diagnosed standard-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) during the remission induction, consolidation/intensification, and maintenance phases always includes combination chemotherapy. Intrathecal chemotherapy is given to prevent the spread of leukemia cells to the brain and spinal cord.

For children with a poor response to treatment who are in remission after remission induction therapy, a stem cell transplant using stem cells from a donor may be done.

For children with a poor response to treatment who are not in remission after remission induction therapy, further treatment is usually the same treatment given to children with high-risk ALL.

Throughout treatment, it's important that your child take all medicines ordered by the doctor. Not taking the medicines as directed increases the chance the cancer will come back.

Treatment of high-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

The treatment of newly diagnosed high-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) during the remission induction, consolidation/intensification, and maintenance phases always includes combination chemotherapy. Children in the high-risk ALL group are given more anticancer drugs and higher doses of anticancer drugs, especially during the consolidation/intensification phase, than children in the standard-risk group.

Intrathecal and systemic chemotherapy are given to prevent or treat the spread of leukemia cells to the brain and spinal cord. Sometimes radiation therapy to the brain is also given.

Throughout treatment, it's important that your child take all medicines ordered by the doctor. Not taking the medicines as directed increases the chance the cancer will come back.

Treatment of very high-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Treatment of newly diagnosed very high-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) during the remission induction, consolidation/intensification, and maintenance phases always includes combination chemotherapy. Children in the very high-risk ALL group are given more anticancer drugs than children in the high-risk group. It is not clear whether a stem cell transplant during first remission will help the child live longer.

Intrathecal and systemic chemotherapy are given to prevent or treat the spread of leukemia cells to the brain and spinal cord. Sometimes radiation therapy to the brain is also given.

Throughout treatment, it's important that your child take all medicines ordered by the doctor. Not taking the medicines as directed increases the chance the cancer will come back.

Treatment of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the brain and spinal cord or testicles

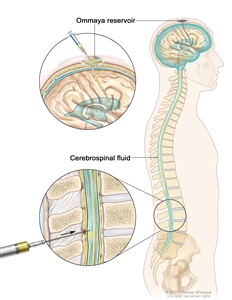

Chemotherapy to kill leukemia cells or prevent them from spreading to the brain and spinal cord (central nervous system; CNS) is called CNS-directed therapy. Standard doses of chemotherapy may not cross the blood-brain barrier to get into the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. Therefore, leukemia cells are able to hide in the CNS. Systemic chemotherapy given in high doses or intrathecal chemotherapy (into the cerebrospinal fluid) is able to reach leukemia cells in the CNS. Sometimes external radiation therapy to the brain is also given.

Intrathecal chemotherapy. Anticancer drugs are injected into the intrathecal space, which is the space that holds the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF, shown in blue). There are two different ways to do this. One way, shown in the top part of the figure, is to inject the drugs into an Ommaya reservoir (a dome-shaped container that is placed under the scalp during surgery; it holds the drugs as they flow through a small tube into the brain). The other way, shown in the bottom part of the figure, is to inject the drugs directly into the CSF in the lower part of the spinal column, after a small area on the lower back is numbed.

These treatments are given in addition to treatment that is used to kill leukemia cells in the rest of the body. All children with ALL receive CNS-directed therapy as part of induction therapy and consolidation/intensification therapy and sometimes during maintenance therapy.

If the leukemia cells spread to the testicles, treatment includes high doses of systemic chemotherapy and sometimes radiation therapy.

Throughout treatment, it's important that your child take all medicines ordered by the doctor. Not taking the medicines as directed increases the chance the cancer will come back.

Treatment of T-cell childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Treatment of newly diagnosed T-cell childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) during the remission induction, consolidation/intensification, and maintenance phases always includes combination chemotherapy. Children with T-ALL are given more anticancer drugs and higher doses of anticancer drugs than children in the newly diagnosed standard-risk group.

Intrathecal and systemic chemotherapy are given to prevent or treat the spread of leukemia cells to the brain and spinal cord. Sometimes radiation therapy to the brain is also given.

Throughout treatment, it's important that your child take all medicine ordered by the doctor. Not taking the medicines as directed increases the chance the cancer will come back.

Treatment of infants with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) diagnosed in infancy is uncommon. Infants with ALL usually have more symptoms and need more medical support when they are diagnosed. They have a higher risk of relapse than older children.

Treatment of infants with newly diagnosed ALL during the remission induction, consolidation/intensification, and maintenance phases always includes combination chemotherapy. Infants with ALL are given different anticancer drugs and higher doses of anticancer drugs than children 1 year and older in the standard-risk group. It is not clear whether a stem cell transplant during first remission will help your child live longer.

Intrathecal and systemic chemotherapy are given to prevent or treat the spread of leukemia cells to the brain and spinal cord.

Throughout treatment, it's important that you give your child all medicines ordered by the doctor. Not giving the medicines as directed increases the chance the cancer will come back.

Treatment of adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Adolescents and young adults are usually considered to have high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Treatment of newly diagnosed ALL in adolescents and young adults during the remission induction, consolidation/intensification, and maintenance phases always includes combination chemotherapy. Adolescents and young adults with ALL are given more anticancer drugs and higher doses of anticancer drugs than children in the standard-risk group.

Intrathecal and systemic chemotherapy are given to prevent or treat the spread of leukemia cells to the brain and spinal cord. Sometimes radiation therapy to the brain is also given.

Throughout treatment, it's important that your child take all medicines ordered by the doctor. Not taking the medicines as directed increases the chance the cancer will come back.

Treatment of children with Down syndrome and acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Treatment of newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in children, adolescents, and young adults with Down syndrome during the remission induction, consolidation/intensification, and maintenance phases always includes combination chemotherapy. Children with Down syndrome and ALL are treated based on their risk group. Children with Down syndrome and ALL may experience more side effects from treatment than other children. Sometimes children with Down syndrome may receive lower doses of anticancer drugs to lower the risk of side effects from treatment.

Intrathecal and systemic chemotherapy are given to prevent or treat the spread of leukemia cells to the brain and spinal cord. Sometimes radiation therapy to the brain is also given.

Throughout treatment, it's important that your child take all medicines ordered by the doctor. Not taking the medicines as directed increases the chance the cancer will come back.

Treatment of childhood Philadelphia chromosome–positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Philadelphia chromosome–positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is uncommon in young children. It occurs more often in adolescence and with increasing age.

Treatment of newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome –positive childhood ALL during the remission induction, consolidation/intensification, and maintenance phases always includes combination chemotherapy. Treatment also includes targeted therapy (imatinib mesylate or dasatinib) with or without a stem cell transplant using stem cells from a donor.

Intrathecal and systemic chemotherapy are given to prevent or treat the spread of leukemia cells to the brain and spinal cord.

Throughout treatment, it's important that your child take all medicines ordered by the doctor. Not taking the medicines as directed increases the chance the cancer will come back.

Treatment of relapsed or refractory childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Refractory childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is cancer that does not respond to initial treatment.

Relapsed childhood ALL is cancer that has come back after it has been treated. The leukemia may come back in the blood and bone marrow, brain, spinal cord, testicles, or other parts of the body.

Treatment of relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) that comes back in the bone marrow may include:

- combination chemotherapy with or without immunotherapy (blinatumomab) and/or targeted therapy

- stem cell transplant, using stem cells from a donor

Other treatments for refractory or relapsed childhood ALL may include:

- targeted therapy (inotuzumab, imatinib, or dasatinib)

- chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy

Treatment of relapsed childhood ALL that comes back outside the bone marrow may include:

- systemic chemotherapy and intrathecal chemotherapy with radiation therapy to the brain and/or spinal cord for cancer that comes back in the brain and spinal cord only

- stem cell transplant for cancer that has relapsed in the brain and/or spinal cord, especially if relapse occurs soon after initial diagnosis

- combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy for cancer that comes back in the testicles only

Prognostic factors for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

If your child has been diagnosed with ALL, you likely have questions about how serious the cancer is and your child's survival. The likely outcome or course of a disease is called prognosis.

The prognosis depends on:

- how quickly and how low the leukemia cell count drops after the first month of treatment

- your child's age at the time of diagnosis, sex, race, and ethnic background

- the number of white blood cells in the blood at the time of diagnosis

- whether the leukemia cells began from B lymphocytes or T lymphocytes

- whether there are certain changes in the chromosomes or genes of the leukemia cells

- whether your child has Down syndrome

- whether leukemia cells are found in the cerebrospinal fluid at diagnosis

- your child's weight at the time of diagnosis and during treatment

For leukemia that comes back after treatment, your child's prognosis depends partly on:

- how long it is between the time of diagnosis and when the leukemia comes back

- whether the leukemia comes back in the bone marrow or in other parts of the body

- your child's age at relapse

- your child's risk group at initial diagnosis

- your child's initial response to treatment for the relapsed leukemia

- whether the leukemia cells began from B lymphocytes or T lymphocytes

- whether there are certain changes in the chromosomes or genes in the leukemia cells

No two people are alike, and responses to treatment can vary greatly. Your child's cancer care team is in the best position to talk with you about your child's prognosis.

Side effects and late effects of treatment

Cancer treatments can cause side effects. Which side effects your child might have depends on the type of treatment they receive, the dose, and how their body reacts. Talk with your child's treatment team about which side effects to look for and ways to manage them.

To learn more about side effects that begin during treatment for cancer, visit Side Effects.

Problems from cancer treatment that begin 6 months or later after treatment and continue for months or years are called late effects.

Late effects of cancer treatment may include:

- Physical problems, including problems with the heart, blood vessels, liver, or bones, and fertility.

- Changes in mood, feelings, thinking, learning, or memory. Children younger than 4 years who have received radiation therapy to the brain have a higher risk of these effects.

- Second cancers (new types of cancer) or other conditions, such as brain tumors, thyroid cancer, acute myeloid leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome.

Some late effects may be treated or controlled. It is important to talk with your child's doctors about the possible late effects caused by some treatments. Learn more about Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer.

Follow-up care

As your child goes through treatment, they will have follow-up tests or check-ups. Some of the tests that were done to diagnose the cancer may be repeated to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Some of the tests will continue to be done from time to time after treatment has ended. The results of these tests can show if your child's condition has changed or if the cancer has recurred (come back).

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy are done during initial phases of treatment to see how well the treatment is working. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy are typically not done after treatment has ended, unless there is concern that the leukemia might have come back.

Learn more about the follow-up tests in Tests to diagnose childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Coping with your child's cancer

When your child has cancer, every member of the family needs support. Taking care of yourself during this difficult time is important. Reach out to your child's treatment team and to people in your family and community for support. To learn more, visit Support for Families: Childhood Cancer and the booklet Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents.

About This PDQ Summary

About PDQ

Physician Data Query (PDQ) is the National Cancer Institute's (NCI's) comprehensive cancer information database. The PDQ database contains summaries of the latest published information on cancer prevention, detection, genetics, treatment, supportive care, and complementary and alternative medicine. Most summaries come in two versions. The health professional versions have detailed information written in technical language. The patient versions are written in easy-to-understand, nontechnical language. Both versions have cancer information that is accurate and up to date and most versions are also available in Spanish.

PDQ is a service of the NCI. The NCI is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH is the federal government's center of biomedical research. The PDQ summaries are based on an independent review of the medical literature. They are not policy statements of the NCI or the NIH.

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary has current information about the treatment of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. It is meant to inform and help patients, families, and caregivers. It does not give formal guidelines or recommendations for making decisions about health care.

Reviewers and Updates

Editorial Boards write the PDQ cancer information summaries and keep them up to date. These Boards are made up of experts in cancer treatment and other specialties related to cancer. The summaries are reviewed regularly and changes are made when there is new information. The date on each summary ("Updated") is the date of the most recent change.

The information in this patient summary was taken from the health professional version, which is reviewed regularly and updated as needed, by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board.

Clinical Trial Information

A clinical trial is a study to answer a scientific question, such as whether one treatment is better than another. Trials are based on past studies and what has been learned in the laboratory. Each trial answers certain scientific questions in order to find new and better ways to help cancer patients. During treatment clinical trials, information is collected about the effects of a new treatment and how well it works. If a clinical trial shows that a new treatment is better than one currently being used, the new treatment may become "standard." Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Clinical trials can be found online at NCI's website. For more information, call the Cancer Information Service (CIS), NCI's contact center, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. The content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text. It cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless the whole summary is shown and it is updated regularly. However, a user would be allowed to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks in the following way: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The best way to cite this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/leukemia/patient/child-all-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389385]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use in the PDQ summaries only. If you want to use an image from a PDQ summary and you are not using the whole summary, you must get permission from the owner. It cannot be given by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the images in this summary, along with many other images related to cancer can be found in Visuals Online. Visuals Online is a collection of more than 3,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used to make decisions about insurance reimbursement. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website's E-mail Us.

Last Revised: 2025-04-15

If you want to know more about cancer and how it is treated, or if you wish to know about clinical trials for your type of cancer, you can call the NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-422-6237, toll free. A trained information specialist can talk with you and answer your questions.