Endometrial Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

General Information About Endometrial Cancer

Cancer of the endometrium is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States and accounts for 7% of all cancers in women. Most cases are diagnosed at an early stage and are amenable to treatment with surgery alone.[1] However, patients with pathological features predictive of a high rate of relapse and patients with extrauterine spread at diagnosis have a high rate of relapse despite adjuvant therapy. The most common cause of death in patients with endometrial cancer is cardiovascular disease because of related metabolic risk factors.[2]

Incidence and Mortality

Estimated new cases and deaths from cancer of the uterine corpus, which includes the endometrium, in the United States in 2025:[1]

- New cases: 69,120.

- Deaths: 13,860.

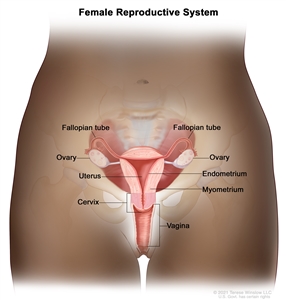

Anatomy

The endometrium is the inner lining of the uterus and has both functional and basal layers. The functional layer is hormonally sensitive and is shed in a cyclical pattern during menstruation in reproductive-age women. Both estrogen and progesterone are necessary to maintain a normal endometrial lining. However, factors that lead to an excess of estrogen, including obesity and anovulation, lead to an increase in the deposition of the endometrial lining. These changes may lead to endometrial hyperplasia and, in some cases, endometrial cancer. Whatever the cause, a thickened lining will lead to sloughing of the endometrial tissue through the endometrial canal and into the vagina. As a result, heavy menstrual bleeding or bleeding after menopause are often the initial signs of endometrial cancer. This symptom tends to happen early in the disease course, allowing for identification of the disease at an early stage for most women.

Anatomy of the female reproductive system.

Risk Factors

Increasing age is the most important risk factor for most cancers. Other risk factors for endometrial cancer include the following:

- Hormone therapy.[3,4,5,6]

- Selective estrogen receptor modifiers.[15,16,17]

- Tamoxifen therapy.

- Obesity.[18,19]

- Metabolic syndrome.[20]

- Diabetes.[21,22]

- Reproductive factors.

- Family history/genetic predisposition.

- Endometrial hyperplasia.[31]

For more information, see Endometrial Cancer Prevention.

Prolonged, unopposed estrogen exposure has been associated with an increased risk of endometrial cancer.[9,32] However, combined estrogen and progesterone therapy prevents this increased risk.[33,34]

Tamoxifen, which is used to treat and prevent breast cancer (NSABP-B-14), is associated with an increased risk of endometrial cancer related to the estrogenic effect of tamoxifen on the endometrium.[15,35] It is important that patients who are receiving tamoxifen and experiencing abnormal uterine bleeding have follow-up examinations and biopsy of the endometrial lining. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration released a black box warning that includes data about the increase in uterine malignancies associated with tamoxifen use. For more information about risk factors for Lynch syndrome–associated endometrial cancer, see the Lynch Syndrome section in Genetics of Breast and Gynecologic Cancers.

Clinical Features

Irregular vaginal bleeding is the most common presenting sign of endometrial cancer. It generally occurs early in the disease process and is the reason why most patients are diagnosed with highly curable stage I endometrial cancer.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The following procedures may be used to detect endometrial cancer:

- Transvaginal ultrasonography.

- Endometrial biopsy.

- Pelvic examination.

- Dilatation and curettage.

- Hysteroscopy.

To definitively diagnose endometrial cancer, a procedure that directly samples the endometrial tissue is necessary.

The Pap smear is not a reliable screening procedure for the detection of endometrial cancer, even though a retrospective study found a strong correlation between positive cervical cytology and high-risk endometrial disease (i.e., high-grade tumor and deep myometrial invasion).[36] A prospective study found a statistically significant association between malignant cytology and increased risk of nodal disease.[37]

Prognostic Factors

Prognostic factors for endometrial cancer include:

Tumor stage and grade (including extrauterine nodal spread)

Table 1 highlights the risk of nodal metastasis based on findings at the time of staging surgery:[38]

| Prognostic Group | Patient Characteristics | Risk of Nodal Involvement |

|---|---|---|

| A | Grade 1 tumors involving only endometrium | <5% |

| No evidence of intraperitoneal spread | ||

| B | Grade 2–3 tumors | 5%–9% pelvic nodes |

| Invasion of <50% of myometrium | ||

| No intraperitoneal spread | 4% para-aortic nodes | |

| C | Deep muscle invasion | 20%–60% pelvic nodes |

| High-grade tumors | 10%–30% para-aortic nodes | |

| Intraperitoneal spread |

A Gynecologic Oncology Group study related surgical-pathological parameters and postoperative treatment to recurrence-free interval and recurrence site. Grade 3 histology and deep myometrial invasion in patients without extrauterine spread were the greatest determinants of recurrence. In this study, the presence of the following factors greatly increased the frequency of recurrence:[39,40]

- Positive pelvic nodes.

- Adnexal metastasis.

- Positive peritoneal cytology.

- Capillary space involvement.

- Involvement of the isthmus or cervix.

- Positive para-aortic nodes (includes all grades and depth of invasion). Of the cases with aortic node metastases, 98% were in patients with positive pelvic nodes, intra-abdominal metastases, or tumor invasion of the outer 33% of the myometrium.

When the only evidence of extrauterine spread is positive peritoneal cytology, the influence on outcome is unclear. The value of therapy directed at this cytological finding is not well founded,[41,42,43,44,45,46] and some data are contradictory.[47] Although the collection of cytology specimens is still suggested, a positive result does not upstage the cancer. Other extrauterine disease must be present before additional postoperative therapy is considered.

Involvement of the capillary-lymphatic space on histopathological examination correlates with extrauterine and nodal spread of tumor.[48]

Hormone receptor status

When possible, progesterone and estrogen receptor statuses, assessed either by biochemical or immunohistochemical methods, are included in the evaluation of patients with stage I and stage II cancer.[49,50,51]

One report found progesterone receptor levels to be the single most important prognostic indicator of 3-year survival in clinical stages I and II disease. Patients with progesterone receptor levels of 100 or greater had a 3-year disease-free survival rate of 93%, compared with 36% for those with a level below 100. After adjusting for progesterone receptor levels, only cervical involvement and peritoneal cytology were significant prognostic variables.[52]

Other reports confirm the importance of hormone receptor status as an independent prognostic factor.[53] Additionally, immunohistochemical staining of paraffin-embedded tissue for both estrogen and progesterone receptors has been shown to correlate with Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique (FIGO) grade and survival.[49,50,51]

Other prognostic factors

Other factors predictive of poor prognosis include:[51,54,55]

- A high S-phase fraction.

- Aneuploidy.

- PTEN loss-of-function variant.

- PIK3CA variant.

- TP53 variant.

- Oncogene expression (e.g., overexpression of the HER2/neu oncogene has been associated with a poor overall prognosis).

A general review of prognostic factors has been published.[56]

References:

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2025. American Cancer Society, 2025. Available online. Last accessed January 16, 2025.

- Ward KK, Shah NR, Saenz CC, et al.: Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among endometrial cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol 126 (2): 176-9, 2012.

- Beral V, Bull D, Reeves G, et al.: Endometrial cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet 365 (9470): 1543-51, 2005 Apr 30-May 6.

- Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al.: Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291 (14): 1701-12, 2004.

- Furness S, Roberts H, Marjoribanks J, et al.: Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women and risk of endometrial hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD000402, 2009.

- Grady D, Gebretsadik T, Kerlikowske K, et al.: Hormone replacement therapy and endometrial cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 85 (2): 304-13, 1995.

- Smith DC, Prentice R, Thompson DJ, et al.: Association of exogenous estrogen and endometrial carcinoma. N Engl J Med 293 (23): 1164-7, 1975.

- Mack TM, Pike MC, Henderson BE, et al.: Estrogens and endometrial cancer in a retirement community. N Engl J Med 294 (23): 1262-7, 1976.

- Ziel HK, Finkle WD: Increased risk of endometrial carcinoma among users of conjugated estrogens. N Engl J Med 293 (23): 1167-70, 1975.

- Walker AM, Jick H: Cancer of the corpus uteri: increasing incidence in the United States, 1970--1975. Am J Epidemiol 110 (1): 47-51, 1979.

- Gray LA, Christopherson WM, Hoover RN: Estrogens and endometrial carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol 49 (4): 385-9, 1977.

- McDonald TW, Annegers JF, O'Fallon WM, et al.: Exogenous estrogen and endometrial carcinoma: case-control and incidence study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 127 (6): 572-80, 1977.

- Antunes CM, Strolley PD, Rosenshein NB, et al.: Endometrial cancer and estrogen use. Report of a large case-control study. N Engl J Med 300 (1): 9-13, 1979.

- Shapiro S, Kelly JP, Rosenberg L, et al.: Risk of localized and widespread endometrial cancer in relation to recent and discontinued use of conjugated estrogens. N Engl J Med 313 (16): 969-72, 1985.

- Fisher B, Costantino JP, Redmond CK, et al.: Endometrial cancer in tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patients: findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-14. J Natl Cancer Inst 86 (7): 527-37, 1994.

- Cummings SR, Eckert S, Krueger KA, et al.: The effect of raloxifene on risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: results from the MORE randomized trial. Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation. JAMA 281 (23): 2189-97, 1999.

- DeMichele A, Troxel AB, Berlin JA, et al.: Impact of raloxifene or tamoxifen use on endometrial cancer risk: a population-based case-control study. J Clin Oncol 26 (25): 4151-9, 2008.

- Bergström A, Pisani P, Tenet V, et al.: Overweight as an avoidable cause of cancer in Europe. Int J Cancer 91 (3): 421-30, 2001.

- Aune D, Navarro Rosenblatt DA, Chan DS, et al.: Anthropometric factors and endometrial cancer risk: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Ann Oncol 26 (8): 1635-48, 2015.

- Esposito K, Chiodini P, Capuano A, et al.: Metabolic syndrome and endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Endocrine 45 (1): 28-36, 2014.

- Troisi R, Potischman N, Hoover RN, et al.: Insulin and endometrial cancer. Am J Epidemiol 146 (6): 476-82, 1997.

- Tsilidis KK, Kasimis JC, Lopez DS, et al.: Type 2 diabetes and cancer: umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. BMJ 350: g7607, 2015.

- Dossus L, Allen N, Kaaks R, et al.: Reproductive risk factors and endometrial cancer: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int J Cancer 127 (2): 442-51, 2010.

- Brown SB, Hankinson SE: Endogenous estrogens and the risk of breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancers. Steroids 99 (Pt A): 8-10, 2015.

- Barry JA, Azizia MM, Hardiman PJ: Risk of endometrial, ovarian and breast cancer in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 20 (5): 748-58, 2014 Sep-Oct.

- Win AK, Reece JC, Ryan S: Family history and risk of endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 125 (1): 89-98, 2015.

- Daniels MS: Genetic testing by cancer site: uterus. Cancer J 18 (4): 338-42, 2012 Jul-Aug.

- Dunlop MG, Farrington SM, Nicholl I, et al.: Population carrier frequency of hMSH2 and hMLH1 mutations. Br J Cancer 83 (12): 1643-5, 2000.

- Lynch HT, Lynch J, Conway T, et al.: Familial aggregation of carcinoma of the endometrium. Am J Obstet Gynecol 171 (1): 24-7, 1994.

- Lu KH, Schorge JO, Rodabaugh KJ, et al.: Prospective determination of prevalence of lynch syndrome in young women with endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol 25 (33): 5158-64, 2007.

- Widra EA, Dunton CJ, McHugh M, et al.: Endometrial hyperplasia and the risk of carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer 5 (3): 233-235, 1995.

- Jick SS, Walker AM, Jick H: Estrogens, progesterone, and endometrial cancer. Epidemiology 4 (1): 20-4, 1993.

- Jick SS: Combined estrogen and progesterone use and endometrial cancer. Epidemiology 4 (4): 384, 1993.

- Bilezikian JP: Major issues regarding estrogen replacement therapy in postmenopausal women. J Womens Health 3 (4): 273-82, 1994.

- van Leeuwen FE, Benraadt J, Coebergh JW, et al.: Risk of endometrial cancer after tamoxifen treatment of breast cancer. Lancet 343 (8895): 448-52, 1994.

- DuBeshter B, Warshal DP, Angel C, et al.: Endometrial carcinoma: the relevance of cervical cytology. Obstet Gynecol 77 (3): 458-62, 1991.

- Larson DM, Johnson KK, Reyes CN, et al.: Prognostic significance of malignant cervical cytology in patients with endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol 84 (3): 399-403, 1994.

- Takeshima N, Hirai Y, Tanaka N, et al.: Pelvic lymph node metastasis in endometrial cancer with no myometrial invasion. Obstet Gynecol 88 (2): 280-2, 1996.

- Morrow CP, Bundy BN, Kurman RJ, et al.: Relationship between surgical-pathological risk factors and outcome in clinical stage I and II carcinoma of the endometrium: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 40 (1): 55-65, 1991.

- Lanciano RM, Corn BW, Schultz DJ, et al.: The justification for a surgical staging system in endometrial carcinoma. Radiother Oncol 28 (3): 189-96, 1993.

- Ambros RA, Kurman RJ: Combined assessment of vascular and myometrial invasion as a model to predict prognosis in stage I endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus. Cancer 69 (6): 1424-31, 1992.

- Turner DA, Gershenson DM, Atkinson N, et al.: The prognostic significance of peritoneal cytology for stage I endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol 74 (5): 775-80, 1989.

- Piver MS, Recio FO, Baker TR, et al.: A prospective trial of progesterone therapy for malignant peritoneal cytology in patients with endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 47 (3): 373-6, 1992.

- Kadar N, Homesley HD, Malfetano JH: Positive peritoneal cytology is an adverse factor in endometrial carcinoma only if there is other evidence of extrauterine disease. Gynecol Oncol 46 (2): 145-9, 1992.

- Lurain JR: The significance of positive peritoneal cytology in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 46 (2): 143-4, 1992.

- Lurain JR, Rice BL, Rademaker AW, et al.: Prognostic factors associated with recurrence in clinical stage I adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol 78 (1): 63-9, 1991.

- Garg G, Gao F, Wright JD, et al.: Positive peritoneal cytology is an independent risk-factor in early stage endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 128 (1): 77-82, 2013.

- Hanson MB, van Nagell JR, Powell DE, et al.: The prognostic significance of lymph-vascular space invasion in stage I endometrial cancer. Cancer 55 (8): 1753-7, 1985.

- Carcangiu ML, Chambers JT, Voynick IM, et al.: Immunohistochemical evaluation of estrogen and progesterone receptor content in 183 patients with endometrial carcinoma. Part I: Clinical and histologic correlations. Am J Clin Pathol 94 (3): 247-54, 1990.

- Chambers JT, Carcangiu ML, Voynick IM, et al.: Immunohistochemical evaluation of estrogen and progesterone receptor content in 183 patients with endometrial carcinoma. Part II: Correlation between biochemical and immunohistochemical methods and survival. Am J Clin Pathol 94 (3): 255-60, 1990.

- Gurpide E: Endometrial cancer: biochemical and clinical correlates. J Natl Cancer Inst 83 (6): 405-16, 1991.

- Ingram SS, Rosenman J, Heath R, et al.: The predictive value of progesterone receptor levels in endometrial cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 17 (1): 21-7, 1989.

- Creasman WT: Prognostic significance of hormone receptors in endometrial cancer. Cancer 71 (4 Suppl): 1467-70, 1993.

- Friberg LG, Norén H, Delle U: Prognostic value of DNA ploidy and S-phase fraction in endometrial cancer stage I and II: a prospective 5-year survival study. Gynecol Oncol 53 (1): 64-9, 1994.

- Hetzel DJ, Wilson TO, Keeney GL, et al.: HER-2/neu expression: a major prognostic factor in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 47 (2): 179-85, 1992.

- Binder PS, Mutch DG: Update on prognostic markers for endometrial cancer. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 10 (3): 277-88, 2014.

Cellular Classification of Endometrial Cancer

Endometrial cancers are classified as one of the following two types:

- Type 1 may arise from complex atypical hyperplasia and is pathogenetically linked to unopposed estrogenic stimulation.

- Type 2 develops from atrophic endometrium and is not linked to hormonally driven pathogenesis.

The most common type of endometrial cancer is endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

Frequency of endometrial cancer cell types is as follows:

- Endometrioid (75%) comprises malignant glandular epithelial elements; an admixture of squamous metaplasia is not uncommon.

- Ciliated adenocarcinoma.

- Secretory adenocarcinoma.

- Papillary and villoglandular adenocarcinomas are histologically similar to those noted in the ovary and the fallopian tube. The prognosis is worse for these tumors.[1]

- Adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation.

- Adenoacanthoma.

- Adenosquamous cells contain malignant glandular and squamous epithelial elements.[2]

- Mixed, defined as two carcinomatous cell types, with the smaller component making up at least 10% of the total (10%).

- Uterine papillary serous (<10%).

- Clear cell (4%) is histologically similar to those noted in the ovary and the fallopian tube. The prognosis for clear cell tumors is worse.[1]

- Carcinosarcoma (3%), also known as malignant mixed mesodermal tumor, has both carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements. This tumor was historically categorized as a subtype of uterine sarcomas; however, recent evidence points to its origin as an adenocarcinoma that has undergone differentiation into the sarcomatous elements.

- Mucinous (1%).

- Squamous cell (<1%).

- Undifferentiated (<1%).

Molecular Subgroups

PTEN variants are more common in type 1 endometrial cancers; TP53 and HER2/neu overexpression are more common in type 2 endometrial cancers, although some overlap exists.

The Cancer Genome Atlas's full genetic display of hundreds of endometrial cancers identified four subtypes to further characterize endometrial cancers:[3]

- POLE ultramutated. This subtype has clinical significance, and adjuvant therapies are avoided.

- Microsatellite instability hypermutated.

- Copy number low.

- Copy number high.

These categories can be used to stratify patients into low- and high-risk prognostic categories. A modification of The Cancer Genome Atlas methods into more accessible tests was also successful in discriminating cancers into relevant prognostic categories. However, a combination of previously known risk factors with the genetic data was the most effective at determining prognostic categories.[4]

References:

- Gusberg SB: Virulence factors in endometrial cancer. Cancer 71 (4 Suppl): 1464-6, 1993.

- Zaino RJ, Kurman R, Herbold D, et al.: The significance of squamous differentiation in endometrial carcinoma. Data from a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer 68 (10): 2293-302, 1991.

- Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, et al.: Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 497 (7447): 67-73, 2013.

- Talhouk A, McConechy MK, Leung S, et al.: A clinically applicable molecular-based classification for endometrial cancers. Br J Cancer 113 (2): 299-310, 2015.

Stage Information for Endometrial Cancer

The pattern of endometrial cancer spread is partially dependent on the degree of cellular differentiation. Well-differentiated tumors tend to limit their spread to the surface of the endometrium; myometrial invasion is less common. Myometrial invasion occurs much more frequently in patients with poorly differentiated tumors and is frequently a harbinger of lymph node involvement and distant metastases.[1,2]

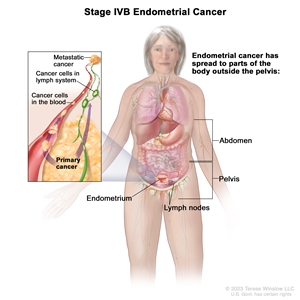

Metastatic spread occurs in a characteristic pattern. Regional spread to the pelvic and para-aortic nodes is common. Distant metastasis most commonly involves the following sites:

- Lungs.

- Inguinal and supraclavicular nodes.

- Liver.

- Bones.

- Brain.

- Vagina.

FIGO Staging

The Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique (FIGO) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) have both designated staging systems for endometrial cancer. The FIGO system is the most commonly used staging system for endometrial cancer.[3,4,5] The 2023 FIGO staging update has not been widely adopted because it incorporates molecular-based results, and some physicians do not have access to those data for their patients. Additionally, given the significant changes in the 2023 FIGO staging system, especially in the definition of early stage disease, more outcome data are needed so it might be more prudent to use the 2021 system in a clinical setting while discussing prognosis and treatment with patients. Therefore, both the 2023 and the 2021 FIGO staging systems are presented in this section.

FIGO stages I to IV are further subdivided by the histological grade (G) of the tumor, for example, stage IB G2. Carcinosarcomas, which had previously been designated as sarcomas, are now considered poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas; as such, they are included in this system.[5]

2023 FIGO staging for endometrial cancer

| Stage | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; p = pathological; AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer; ESGO-ESTRO-ESP = European Society of Gynaecological Oncology, European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology, European Society of Pathology; FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique; ITC = isolated tumor cell; LVSI = lymphovascular space involvement; MMRd = mismatch repair deficiency; NSMP = no specific molecular profile;POLEmut= pathogenicPOLEmutation; p53abn =TP53abnormal; SLN = sentinel lymph node; WHO = World Health Organization. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.[3] | ||

| b Endometrial cancer is surgically staged and pathologically examined. In all stages, the grade of the lesion, the histological type and LVSI must be recorded. If available and feasible, molecular classification testing (POLEmut, MMRd, NSMP, p53abn) is encouraged in all patients with endometrial cancer for prognostic risk-group stratification and as factors that might influence adjuvant and systemic treatment decisions (seeTable 6). | ||

| c In early endometrial cancer, the standard surgery is a total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy via a minimally invasive laparoscopic approach. Staging procedures include infracolic omentectomy in specific histological subtypes, such as serous and undifferentiated endometrial carcinoma, as well as carcinosarcoma, due to the high risk of microscopic omental metastases. Lymph node staging should be performed in patients with intermediate-high/high-risk disease. SLN biopsy is an adequate alternative to systematic lymphadenectomy for staging proposes. SLN biopsy can also be considered in patients with low−/low-intermediate-risk disease to rule out occult lymph node metastases and to identify disease truly confined to the uterus. Thus, the ESGO-ESTRO-ESP guidelines allow an approach of SLN in all patients with endometrial carcinoma, which is endorsed by FIGO. In assumed early endometrial cancer, an SLN biopsy in an adequate alternative to systematic lymphadenectomy in high-intermediate and high-risk cases for the purpose of lymph node staging and can also be considered in low–/intermediate-risk disease to rule out occult lymph node metastases. An SLN biopsy should be done in association with thorough (ultrastaging) staging as it will increase the detection of low-volume disease in lymph nodes. | ||

| d Low-grade endometrioid carcinomas involving both the endometrium and the ovary are considered to have a good prognosis, and no adjuvant treatment is recommended if all the below criteria are met. Disease limited to low-grade endometrioid carcinomas involving the endometrium and ovaries (Stage IA3) must be distinguished from extensive spread of the endometrial carcinoma to the ovary (Stage IIIA1), by the following criteria: (1) no more than superficial myometrial invasion is present (<50%); (2) absence of extensive/substantial LVSI; (3) absence of additional metastases; and (4) the ovarian tumor is unilateral, limited to the ovary, without capsule invasion/rupture (equivalent to pT1a). | ||

| e LVSI as defined in WHO 2021: extensive/substantial, ≥5 vessels involved. | ||

| f Grade and histological type are as follows: (1) Serous adenocarcinomas, clear cell adenocarcinomas, mesonephric-like carcinomas, gastrointestinal-type mucinous endometrial carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinomas, and carcinosarcomas are considered high grade by definition. For endometrioid carcinomas, grade is based on the proportion of solid areas: low grade = grade 1 (≤5%) and grade 2 (6%–50%); and high grade = grade 3 (>50%). Nuclear atypia excessive for the grade raises the grade of a grade 1 or 2 tumor by one. The presence of unusual nuclear atypia in an architecturally low-grade tumor should prompt the evaluation ofTP53and consideration of serous carcinoma. Adenocarcinomas with squamous differentiation are graded according to the microscopic features of the glandular component; (2) Nonaggressive histological types are composed of low-grade (grade 1 and 2) endometrioid carcinomas. Aggressive histological types are composed of high-grade endometrioid carcinomas (grade 3), serous, clear cell, undifferentiated, mixed, mesonephric-like, gastrointestinal mucinous type carcinomas, and carcinosarcomas; and (3) It should be noted that high-grade endometrioid carcinomas (grade 3) are a prognostically, clinically, and molecularly heterogenous disease, and the tumor type that benefits most from applying molecular classification for improved prognostication and for treatment decision-making. Without molecular classification, high-grade endometrioid carcinomas cannot appropriately be allocated to a risk group, and thus, molecular profiling is particularly recommended in these patients. For practical purposes and to avoid undertreatment of patients, if the molecular classification is unknown, high-grade endometrioid carcinomas were grouped together with the aggressive histological types in the actual FIGO classification. | ||

| g Micrometastases are considered to be metastatic involvement (pN1 [mi]). The prognostic significance of ITCs is unclear. The presence of ITCs should be documented and is regarded as pN0(I+). According to the AJCC 8th edition staging, macrometastases are >2 mm in size, micrometastases are >0.2–2 mm and/or >200 cells, and ITCs are ≤0.2 mm and ≤200 cells. These definitions are based on staging established by FIGO and the 8th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. | ||

| I | Confined to the uterine corpus and ovary.d | |

| IA | Disease limited to the endometrium OR nonaggressive histological type, i.e., low-grade endometrioid, with invasion of less than half of myometrium with no or focal LVSI OR good prognosis disease. | |

| IA1 | Nonaggressive histological type limited to an endometrial polyp OR confined to the endometrium. | |

| IA2 | Nonaggressive histological types involving less than half of the myometrium with no or focal LVSI. | |

| IA3 | Low-grade endometrioid carcinomas limited to the uterus and ovary.d | |

| IB | Nonaggressive histological types with invasion of half or more of the myometrium, and with no or focal LVSI.e | |

| IC | Aggressive histological typesf limited to a polyp or confined to the endometrium. | |

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique; LVSI = lymphovascular space involvement. | |

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.[3] | |

| For the explanations for footnotesb−f, seeTable 2. | |

| II | Invasion of cervical stroma without extrauterine extension OR with substantial LVSI OR aggressive histological types with myometrial invasion. |

| IIA | Invasion of the cervical stroma of nonaggressive histological types. |

| IIB | Substantial LVSIe of nonaggressive histological types. |

| IIC | Aggressive histological typesf with any myometrial involvement. |

| Stage | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.[3] | ||

| For the explanations for footnotesb−d andg, seeTable 2. | ||

| III | Local and/or regional spread of the tumor of any histological subtype. | |

| IIIA | Invasion of uterine serosa, adnexa, or both by direct extension or metastasis. | |

| IIIA1 | Spread to ovary or fallopian tube (except when meeting stage IA3 criteria).d | |

| IIIA2 | Involvement of uterine subserosa or spread through the uterine serosa. | |

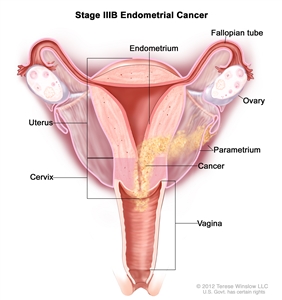

| IIIB | Metastasis or direct spread to the vagina and/or to the parametria or pelvic peritoneum. | |

| IIIB1 | Metastasis or direct spread to the vagina and/or the parametria. | |

| IIIB2 | Metastasis to the pelvic peritoneum. | |

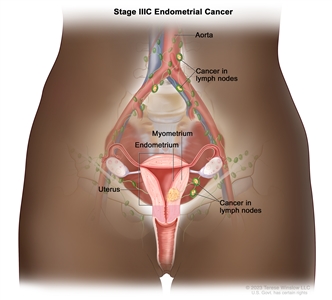

| IIIC | Metastasis to the pelvic or para-aortic lymph nodes or both.g | |

| IIIC1 | Metastasis to the pelvic lymph nodes. | |

| IIIC1i | Micrometastasis. | |

| IIIC1ii | Macrometastasis. | |

| IIIC2 | Metastasis to para-aortic lymph nodes up to the renal vessels, with or without metastasis to the pelvic lymph nodes. | |

| IIIC2i | Micrometastasis. | |

| IIIC2ii | Macrometastasis. | |

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | |

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.[3] | |

| For the explanations for footnotesb−c, seeTable 2. | |

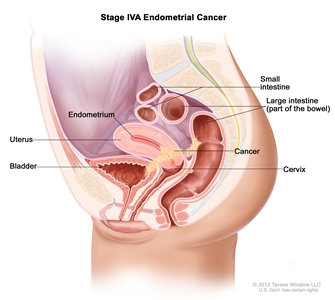

| IV | Spread to the bladder mucosa and/or intestinal mucosa and/or distance metastasis. |

| IVA | Invasion of the bladder mucosa and/or the intestinal/bowel mucosa. |

| IVB | Abdominal peritoneal metastasis beyond the pelvis. |

| IVC | Distant metastasis, including metastasis to any extra- or intra-abdominal lymph nodes above the renal vessels, lungs, liver, brain, or bone. |

| Stage Designation | Molecular Findings in Patients With Early Endometrial Cancer (Stages I and II After Surgical Staging) |

|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique; LVSI = lymphovascular space involvement; MMRd = mismatch repair deficiency; MSI = microsatellite instability; NSMP = no specific molecular profile;POLEmut= pathogenicPOLEmutation; p53abn =TP53abnormal. | |

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.[3] | |

| b When feasible, the addition of molecular subtype to the staging criteria allows a better prediction of prognosis in a staging/prognosis scheme. The performance of complete molecular classification (POLEmut, MMRd, NSMP, p53abn) is encouraged in all cases of endometrial cancer for prognostic risk-group stratification and as potential influencing factors of adjuvant or systemic treatment decisions. Molecular subtype assignment can be done on a biopsy, in which case it need not be repeated on the hysterectomy specimen. When performed, these molecular classifications should be recorded in all stages. A pathogenicPOLEmutation (POLEmut) is associated with a good prognosis. MMRd or MSI and NSMP are associated with an intermediate prognosis. AbnormalTP53(p53abn) is associated with a poor prognosis. When the molecular classification is known the staging is modified as follows: (1) FIGO Stages I and II are based on surgical/anatomical and histological findings. In case the molecular classification revealsPOLEmutor p53abn status, the FIGO stage is modified in the early stage of the disease. This is depicted in the FIGO stage by the addition of "m" for molecular classification, and a subscript is added to denotePOLEmutor p53abn status, as shown in the table. MMRd or NSMP status do not modify early FIGO stages; however, these molecular classifications should be recorded for the purpose of data collection. When molecular classification reveals MMRd or NSMP, it should be recorded as Stage ImMMRd or Stage ImNSMP and Stage IImMMRd or Stage IImNSMP; (2) FIGO Stages III and IV are based on surgical/anatomical findings. The stage category is not modified by molecular classification; however, the molecular classification should be recorded if known. When the molecular classification is known, it should be recorded as Stage IIIm or Stage IVm with the appropriate subscript for the purpose of data collection. For example, when molecular classification reveals p53abn, it should be recorded as Stage IIImp53abn or Stage IVmp53abn. | |

| IAmPOLEmut | POLEmutendometrial carcinoma, confined to the uterine corpus or with cervical extension, regardless of the degree of LVSI or histological type. |

| IICmp53abn | p53abn endometrial carcinoma confined to the uterine corpus with any myometrial invasion, with or without cervical invasion, and regardless of the degree of LVSI or histological type. |

2021 FIGO staging for endometrial cancer

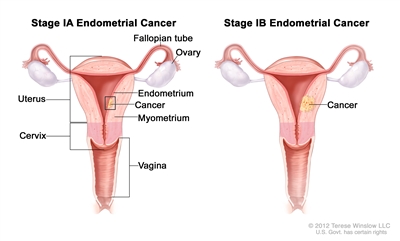

| Stage | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.[4] | ||

| b G1, G2, or G3 (G = grade). | ||

| Ib | Tumor confined to the corpus uteri. |  |

| IAb | No or less than half myometrial invasion. | |

| IBb | Invasion equal to or more than half of the myometrium. | |

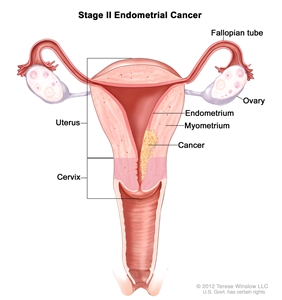

| Stage | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.[4] | ||

| b G1, G2, or G3 (G = grade). | ||

| c Endocervical glandular involvement is considered stage I; it is no longer considered stage II. | ||

| IIb | Tumor invades cervical stroma but does not extend beyond the uterus.c |  |

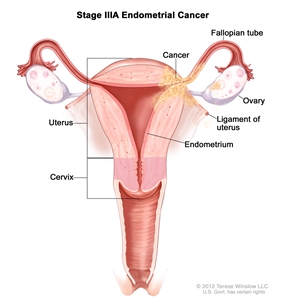

| Stage | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.[4] | ||

| b G1, G2, or G3 (G = grade). | ||

| c Positive cytology has to be reported separately without changing the stage. | ||

| IIIb | Local and/or regional spread of the tumor. | |

| IIIAb | Tumor invades the serosa of the corpus uteri and/or adnexae.c |  |

| IIIBb | Vaginal and/or parametrial involvement.c |  |

| IIICb | Metastases to pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes.c |  |

| IIIC1b | Positive pelvic nodes. | |

| IIIC2b | Positive para-aortic lymph nodes with or without positive pelvic lymph nodes. | |

| Stage | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.[4] | ||

| b G1, G2, or G3 (G = grade). | ||

| IVb | Tumor invades bladder and/or bowel mucosa, and/or distant metastases. | |

| IVAb | Tumor invasion of bladder and/or bowel mucosa. |  |

| IVBb | Distant metastases, including intra-abdominal metastases and/or inguinal lymph nodes. |  |

References:

- Hendrickson M, Ross J, Eifel PJ, et al.: Adenocarcinoma of the endometrium: analysis of 256 cases with carcinoma limited to the uterine corpus. Pathology review and analysis of prognostic variables. Gynecol Oncol 13 (3): 373-92, 1982.

- Nori D, Hilaris BS, Tome M, et al.: Combined surgery and radiation in endometrial carcinoma: an analysis of prognostic factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 13 (4): 489-97, 1987.

- Berek JS, Matias-Guiu X, Creutzberg C, et al.: FIGO staging of endometrial cancer: 2023. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 162 (2): 383-394, 2023.

- Koskas M, Amant F, Mirza MR, et al.: Cancer of the corpus uteri: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 155 (Suppl 1): 45-60, 2021.

- Corpus uteri – carcinoma and carcinosarcoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 661-69.

Treatment Option Overview for Endometrial Cancer

The degree of tumor differentiation has an important effect on the natural history of this disease and on treatment selection.

Patients with endometrial cancer who have localized disease are usually cured. Best results are obtained with one of two standard treatments:

- Hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

- Hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and adjuvant radiation therapy (when deep invasion of the myometrial muscle [more than 50% of the myometrium] or grade 3 tumor with myometrial invasion is present).

Patients with regional and distant metastases are rarely cured, although they are occasionally responsive to standard hormone therapy.

Progestational agents have been evaluated as adjuvant therapy in several randomized trials. A meta-analysis by the Cochrane group confirms no clinical benefit to adjuvant progestogens in clinical stage I disease.[1][Level of evidence A1]

The treatment options for each stage of endometrial cancer are presented in Table 11.

| Stage (FIGO Staging Definitions) | Treatment Options | |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| Stage I and stage II endometrial cancer | Grades 1 and 2 | Surgery with or without lymph node sampling |

| Postoperative vaginal brachytherapy | ||

| Radiation therapy alone | ||

| Grade 3 (includes serous, clear cell, and carcinosarcoma) | Surgery | |

| Postoperative chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy | ||

| Stage III, stage IV, and recurrent endometrial cancer | Operable disease | Surgery followed by chemotherapy or radiation therapy |

| Inoperable disease | Chemotherapy and radiation therapy | |

| Inoperable disease in which the patient is not a candidate for radiation therapy | Hormone therapy | |

| Biological therapy | ||

| Advanced or recurrent disease | Immunotherapy | |

| Clinical trials | ||

References:

- Martin-Hirsch PP, Bryant A, Keep SL, et al.: Adjuvant progestagens for endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (6): CD001040, 2011.

Treatment of Stage I and Stage II Endometrial Cancer

Treatment Options for Stage I and Stage II Endometrial Cancer

Treatment of stage I and stage II endometrial cancer depends on the grade and histological type.

In the current Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique (FIGO) staging system, stage II describes tumor that invades the cervical stroma; this is equivalent to the prior stage IIB. Almost all randomized trials for early-stage cancer excluded stage IIB patients. As a result, there is a paucity of quality data on which to base clinical decisions for patients with stage II endometrial cancer.

Low-risk histology:

Grades 1 and 2 tumors are considered low-risk unless they have serous or clear cell histologies.

Treatment options for patients with low-risk histological subtypes of stage I endometrial cancer include:

- Surgery: Hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and possible lymph node dissection.

- Postoperative vaginal brachytherapy.

- Radiation therapy alone.

Most patients do well with surgery alone. However, patients with stage I disease who have high-risk histologies are at a greater risk of recurrence and are eligible for adjuvant therapy.

High-risk histology:

Grade 3 tumors of any histology and any serous tumors, clear cell tumors, or carcinosarcomas are considered high-risk.

Treatment options for patients with stage I or stage II endometrial cancer who have high-risk histologies include:

- Surgery: Hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, with pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection.

- Postoperative chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy.

Patients with serous or clear cell histologies have higher rates of recurrence than do patients with other stage I or stage II endometrioid carcinomas. Management guidelines are based on the outcomes reported in institutional case series that used a regimen of adjuvant carboplatin plus paclitaxel, and occasionally, radiation therapy for patients with this histological subtype.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]

Carcinosarcomas have been evaluated in clinical trials both separately and with other sarcomas because of their prior designation in this group. In a nonrandomized Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study of patients with stage I or II carcinosarcomas, patients who underwent pelvic radiation therapy had a significant reduction in recurrences within the radiation treatment field but no improvement in survival.[10] One nonrandomized study that predominantly included patients with carcinosarcomas appeared to show benefit for adjuvant therapy with cisplatin and doxorubicin.[11]

Surgery

If the uterine cervix is involved, patients may consider one or more of the following options:

- Standard hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, followed by adjuvant radiation therapy.

- Radical hysterectomy.

- Pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection.

Single-institution reviews suggest that radical hysterectomy is more beneficial than standard hysterectomy in cases of cervical involvement of the tumor.[12,13,14]

Surgery with or without lymph node sampling

Table 12 highlights the risk of nodal metastasis based on findings at the time of staging surgery:[15]

| Prognostic Group | Patient Characteristics | Risk of Nodal Involvement |

|---|---|---|

| A | Grade 1 tumors involving only endometrium | <5% |

| No evidence of intraperitoneal spread | ||

| B | Grade 2–3 tumors | 5%–9% pelvic nodes |

| Invasion of <50% of myometrium | ||

| No intraperitoneal spread | 4% para-aortic nodes | |

| C | Deep muscle invasion | 20%–60% pelvic nodes |

| High-grade tumors | 10%–30% para-aortic nodes | |

| Intraperitoneal spread |

For patients in Group A, lymph node dissection has limited utility. Conversely, full pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection is important for patients in Group C, given the likelihood of positive findings. The difficulty lies in determining how to manage patients in Group B.

There are several accepted surgical approaches for patients with presumed stage I endometrial cancer, with intermediate risk for lymphatic spread.

Both retrospective and prospective data support stratifying patients with presumed stage I endometrial cancer into two groups based on the following characteristics:

- Low risk: Well-differentiated or moderately differentiated tumor and/or depth of myometrial invasion is less than 50% and/or tumor is smaller than 2 cm.

- High risk: Poorly differentiated tumor and/or depth of myometrial invasion is 50% or more and/or tumor is 2 cm or larger.

Evidence (lymph node dissection):

- In two studies, patients with low-risk cancer had a sufficiently low risk of lymph node metastasis such that lymph node sampling could be omitted. For patients meeting high-risk criteria, a full pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection was suggested, given patterns of lymphatic spread.[16,17]

- An alternative strategy is the use of sentinel lymph node dissection in patients with presumed stage I endometrial cancer.[18] Although this strategy has been widely adopted at various academic centers, a prospective multicenter trial to determine the false-negative rate for this protocol is lacking. For cases in which isolated tumor cells are identified using the sentinel lymph node approach, it is unclear whether treatment is necessary.

- In patients with high-risk histology (serous, clear cell, carcinosarcoma, or undifferentiated tumors), hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection is the standard approach.

- Laparotomy has been the standard surgical approach. However, laparoscopy is now favored because of the improvement in patients' postoperative recovery without significant impact on outcomes.

Evidence (treatment or surgical staging using laparoscopy vs. laparotomy):

- For patients with early-stage endometrial cancer, several randomized trials have compared total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) with the standard open procedure, total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH). Feasibility of the laparoscopic approach has been confirmed, but this approach is associated with a longer operative time.[15,19,20] TLH has an improved [15,19] or similar [20] adverse event profile and a shorter hospital stay [15,19,20] than does TAH.

- A GOG trial (GOG-LAP2) randomly assigned 2,616 patients with clinical stages I to IIA disease in a 2:1 ratio to comprehensive surgical staging via laparoscopy or laparotomy.[22][Level of evidence A1]

Time to recurrence was the primary end point, with noninferiority defined as a difference in recurrence rate of less than 5.3% between the two groups at 3 years.

- The recurrence rate at 3 years was 10.24% for patients in the laparotomy arm and 11.39% for patients in the laparoscopy arm, with an estimated difference between groups of 1.14% (90% lower bound, -1.278; 95% upper bound, 3.996).

- Although this difference was lower than the prespecified limit, the statistical requirements for noninferiority were not met because of fewer-than-expected recurrences in both groups.

- The 5-year overall survival (OS) rate was 89.8% in both groups.

- The recurrence rate at 3 years was 10.24% for patients in the laparotomy arm and 11.39% for patients in the laparoscopy arm, with an estimated difference between groups of 1.14% (90% lower bound, -1.278; 95% upper bound, 3.996).

- A Cochrane review of the use of laparoscopic staging included four randomized controlled trials that reported OS and progression-free survival (PFS). Ninety percent of the patients were from the GOG-LAP2 trial.[23][Level of evidence A1]

- Overall, laparoscopy and laparotomy were associated with similar OS and PFS rates.

Future analyses may determine whether there are subgroups of patients for whom there is a clinically significant decrement when laparoscopic staging is used.[22][Level of evidence B1]

Postoperative vaginal brachytherapy

Adjuvant radiation therapy reduces the incidence of local and regional recurrence. However, improved survival rates have not been confirmed, and radiation therapy increased toxicity.[24,25,26,27,28] Vaginal cuff brachytherapy is associated with less radiation-related morbidity than is external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) and has been shown to be equivalent to EBRT in the short term for patients with stage I disease.[29] However, long-term follow up of a randomized trial comparing EBRT plus vaginal brachytherapy (VBT) to VBT alone found decreased OS and increased toxicity in the EBRT plus VBT arm.[30]

Evidence (VBT):

- Results of two randomized trials that used adjuvant radiation therapy in patients with stage I disease did not show improved survival but did show reduced locoregional recurrence (3%–4% in the radiation therapy group vs. 12%–14% in the control group after median follow-up of 5–6 years; P < .001), with an increase in side effects.[27,31,32][Level of evidence B1]

- Results of a study by the Danish Endometrial Cancer Group suggest that the absence of radiation therapy does not improve the survival of patients with stage I intermediate-risk disease (grades 1 and 2 with >50% myometrial invasion or grade 3 with <50% myometrial invasion).[33]

- The PORTEC-2 trial (NCT00411138) randomly assigned patients with stage I endometrial cancer who did not undergo lymph node dissection to undergo VBT or EBRT, with prevention of vaginal recurrence as the primary outcome.[29,34][Level of evidence A1]

- At 5 years, there was no difference in the rates of vaginal recurrence, locoregional recurrence, PFS, or OS (84.8% [95% confidence interval (CI), 79.3%–90.3%] for VBT vs. 79.6% [95% CI, 71.2%–88.0%] for EBRT; P = .57).

- The VBT group had significantly fewer gastrointestinal toxic effects and improved quality of life, making VBT the preferred option for adjuvant treatment of patients with stage I disease.

- The Norwegian Radium Hospital trial included 568 patients with clinical stage I endometrial cancer between 1968 and 1974 (before FIGO surgical staging was initiated).[30][Level of evidence A1] After hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, patients were randomly assigned to receive either EBRT and VBT or VBT alone.

- An updated report presenting over 20 years of follow-up data showed no difference in OS between the treatment groups. Median OS was 20.5 years in the EBRT/VBT group and 20.48 in the VBT-alone group (P = .186). In all women, there was an increased risk of secondary cancers after EBRT (hazard ratio [HR], 1.42; 95% CI, 1.01–2.0).

- A post hoc subset analysis of women younger than 60 years at the time of trial registration showed increased mortality in the EBRT/VBT arm (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.06–1.76). Further, the risk of secondary cancers doubled in this group (HR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.3–3.15).

Postoperative radiation therapy

If the cervix is not clinically involved, but extension to the cervix is noted on postoperative pathology, radiation therapy is considered.[22][Level of evidence A1]

Radiation therapy alone

Patients who have medical contraindications to surgery may be treated with radiation therapy alone, but cure rates may be lower than those attained with surgery.[35,36,37]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Kiess AP, Damast S, Makker V, et al.: Five-year outcomes of adjuvant carboplatin/paclitaxel chemotherapy and intravaginal radiation for stage I-II papillary serous endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 127 (2): 321-5, 2012.

- Boruta DM, Gehrig PA, Fader AN, et al.: Management of women with uterine papillary serous cancer: a Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) review. Gynecol Oncol 115 (1): 142-53, 2009.

- Huh WK, Powell M, Leath CA, et al.: Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: comparisons of outcomes in surgical Stage I patients with and without adjuvant therapy. Gynecol Oncol 91 (3): 470-5, 2003.

- Fader AN, Drake RD, O'Malley DM, et al.: Platinum/taxane-based chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy favorably impacts survival outcomes in stage I uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Cancer 115 (10): 2119-27, 2009.

- Kelly MG, O'malley DM, Hui P, et al.: Improved survival in surgical stage I patients with uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) treated with adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol 98 (3): 353-9, 2005.

- Havrilesky LJ, Secord AA, Bae-Jump V, et al.: Outcomes in surgical stage I uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 105 (3): 677-82, 2007.

- Dietrich CS, Modesitt SC, DePriest PD, et al.: The efficacy of adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy in Stage I uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC). Gynecol Oncol 99 (3): 557-63, 2005.

- Townamchai K, Berkowitz R, Bhagwat M, et al.: Vaginal brachytherapy for early stage uterine papillary serous and clear cell endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 129 (1): 18-21, 2013.

- Barney BM, Petersen IA, Mariani A, et al.: The role of vaginal brachytherapy in the treatment of surgical stage I papillary serous or clear cell endometrial cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 85 (1): 109-15, 2013.

- Hornback NB, Omura G, Major FJ: Observations on the use of adjuvant radiation therapy in patients with stage I and II uterine sarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 12 (12): 2127-30, 1986.

- Peters WA, Rivkin SE, Smith MR, et al.: Cisplatin and adriamycin combination chemotherapy for uterine stromal sarcomas and mixed mesodermal tumors. Gynecol Oncol 34 (3): 323-7, 1989.

- Ayhan A, Taskiran C, Celik C, et al.: The long-term survival of women with surgical stage II endometrioid type endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 93 (1): 9-13, 2004.

- Eltabbakh GH, Moore AD: Survival of women with surgical stage II endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 74 (1): 80-5, 1999.

- Orezzoli JP, Sioletic S, Olawaiye A, et al.: Stage II endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium: clinical implications of cervical stromal invasion. Gynecol Oncol 113 (3): 316-23, 2009.

- Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, et al.: Laparoscopy compared with laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group Study LAP2. J Clin Oncol 27 (32): 5331-6, 2009.

- Mariani A, Dowdy SC, Cliby WA, et al.: Prospective assessment of lymphatic dissemination in endometrial cancer: a paradigm shift in surgical staging. Gynecol Oncol 109 (1): 11-8, 2008.

- Mariani A, Webb MJ, Keeney GL, et al.: Low-risk corpus cancer: is lymphadenectomy or radiotherapy necessary? Am J Obstet Gynecol 182 (6): 1506-19, 2000.

- Barlin JN, Khoury-Collado F, Kim CH, et al.: The importance of applying a sentinel lymph node mapping algorithm in endometrial cancer staging: beyond removal of blue nodes. Gynecol Oncol 125 (3): 531-5, 2012.

- Janda M, Gebski V, Brand A, et al.: Quality of life after total laparoscopic hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy for stage I endometrial cancer (LACE): a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 11 (8): 772-80, 2010.

- Mourits MJ, Bijen CB, Arts HJ, et al.: Safety of laparoscopy versus laparotomy in early-stage endometrial cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 11 (8): 763-71, 2010.

- Kornblith AB, Huang HQ, Walker JL, et al.: Quality of life of patients with endometrial cancer undergoing laparoscopic international federation of gynecology and obstetrics staging compared with laparotomy: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 27 (32): 5337-42, 2009.

- Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, et al.: Recurrence and survival after random assignment to laparoscopy versus laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group LAP2 Study. J Clin Oncol 30 (7): 695-700, 2012.

- Galaal K, Bryant A, Fisher AD, et al.: Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the management of early stage endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9: CD006655, 2012.

- Aalders J, Abeler V, Kolstad P, et al.: Postoperative external irradiation and prognostic parameters in stage I endometrial carcinoma: clinical and histopathologic study of 540 patients. Obstet Gynecol 56 (4): 419-27, 1980.

- Morrow CP, Bundy BN, Kurman RJ, et al.: Relationship between surgical-pathological risk factors and outcome in clinical stage I and II carcinoma of the endometrium: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 40 (1): 55-65, 1991.

- Marchetti DL, Caglar H, Driscoll DL, et al.: Pelvic radiation in stage I endometrial adenocarcinoma with high-risk attributes. Gynecol Oncol 37 (1): 51-4, 1990.

- Creutzberg CL, van Putten WL, Koper PC, et al.: Surgery and postoperative radiotherapy versus surgery alone for patients with stage-1 endometrial carcinoma: multicentre randomised trial. PORTEC Study Group. Post Operative Radiation Therapy in Endometrial Carcinoma. Lancet 355 (9213): 1404-11, 2000.

- Kong A, Johnson N, Kitchener HC, et al.: Adjuvant radiotherapy for stage I endometrial cancer: an updated Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 104 (21): 1625-34, 2012.

- Nout RA, Smit VT, Putter H, et al.: Vaginal brachytherapy versus pelvic external beam radiotherapy for patients with endometrial cancer of high-intermediate risk (PORTEC-2): an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised trial. Lancet 375 (9717): 816-23, 2010.

- Onsrud M, Cvancarova M, Hellebust TP, et al.: Long-term outcomes after pelvic radiation for early-stage endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol 31 (31): 3951-6, 2013.

- Keys HM, Roberts JA, Brunetto VL, et al.: A phase III trial of surgery with or without adjunctive external pelvic radiation therapy in intermediate risk endometrial adenocarcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 92 (3): 744-51, 2004.

- Scholten AN, van Putten WL, Beerman H, et al.: Postoperative radiotherapy for Stage 1 endometrial carcinoma: long-term outcome of the randomized PORTEC trial with central pathology review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 63 (3): 834-8, 2005.

- Bertelsen K, Ortoft G, Hansen ES: Survival of Danish patients with endometrial cancer in the intermediate-risk group not given postoperative radiotherapy: the Danish Endometrial Cancer Study (DEMCA). Int J Gynecol Cancer 21 (7): 1191-9, 2011.

- Nout RA, Putter H, Jürgenliemk-Schulz IM, et al.: Five-year quality of life of endometrial cancer patients treated in the randomised Post Operative Radiation Therapy in Endometrial Cancer (PORTEC-2) trial and comparison with norm data. Eur J Cancer 48 (11): 1638-48, 2012.

- Eltabbakh GH, Piver MS, Hempling RE, et al.: Excellent long-term survival and absence of vaginal recurrences in 332 patients with low-risk stage I endometrial adenocarcinoma treated with hysterectomy and vaginal brachytherapy without formal staging lymph node sampling: report of a prospective trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 38 (2): 373-80, 1997.

- Stokes S, Bedwinek J, Kao MS, et al.: Treatment of stage I adenocarcinoma of the endometrium by hysterectomy and adjuvant irradiation: a retrospective analysis of 304 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 12 (3): 339-44, 1986.

- Grigsby PW, Kuske RR, Perez CA, et al.: Medically inoperable stage I adenocarcinoma of the endometrium treated with radiotherapy alone. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 13 (4): 483-8, 1987.

Treatment of Stage III, Stage IV, and Recurrent Endometrial Cancer

Treatment Options for Stage III, Stage IV, and Recurrent Endometrial Cancer

Treatment options for patients with stage III, stage IV, and recurrent endometrial cancer include:

- Surgery followed by chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

- Chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

- Hormone therapy.

- Biological therapy.

- Immunotherapy.

- Clinical trials.

Treatment of patients with stage IV endometrial cancer is dictated by the site of metastatic disease and symptoms related to disease sites.

Surgery followed by chemotherapy or radiation therapy

In general, patients with stage III or stage IV endometrial cancer are treated with surgery, followed by chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both. Observational studies support maximal cytoreductive surgery for patients with stage IV disease, although these conclusions need to be interpreted with care because of the small number of cases and likely selection bias.[1,2]

For many years, radiation therapy was the standard adjuvant treatment for patients with endometrial cancer. However, several randomized trials have confirmed improved survival when adjuvant chemotherapy is used instead of radiation therapy.

Doxorubicin was historically the most active anticancer agent used, with useful but temporary responses obtained in as many as 33% of patients with recurrent disease. Paclitaxel, when combined with platinum chemotherapy or when used as a single agent, also has significant anticancer activity.[3]

Evidence (surgery followed by chemotherapy or radiation therapy):

- Several randomized trials by the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) have used doxorubicin because of its known antitumor activity.[4]

- Adding cisplatin to doxorubicin increased response rates and progression-free survival (PFS) when compared with doxorubicin alone. However, adding cisplatin did not affect overall survival (OS).

- A three-drug regimen of doxorubicin, cisplatin, and paclitaxel with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) was significantly superior to cisplatin and doxorubicin, as shown by the following results:[5,6][Level of evidence B3]

- Response rate was 57% with the three-drug regimen, compared with 34% with the cisplatin and doxorubicin regimen.

- PFS was 8.3 months with the three-drug regimen, compared with 5.3 months with the cisplatin and doxorubicin regimen.

- OS was 15.3 months with the three-drug regimen, compared with 12.3 months with the cisplatin and doxorubicin regimen.

- The 3-drug regimen was associated with grade 3 peripheral neuropathy in 12% of patients and grade 2 peripheral neuropathy in 27% of patients.

Given the toxicity and limited efficacy of these regimens, other treatment options have been widely sought. Several observational studies [7,8] and phase II studies [9,10,11,12] suggest clinical activity with the combination of platinum chemotherapy and paclitaxel in patients with endometrial cancer and measurable disease either after primary surgery or at recurrence.

- The phase III, randomized, open-label, noninferiority GOG-0209 trial (NCT000063999) compared the combination of paclitaxel, doxorubicin, cisplatin (TAP), and G-CSF with carboplatin and paclitaxel (TC) in 1,381 women.[13]

- The median OS was 37 months for patients in the TC group and 41 months for patients in the TAP group (hazard ratio [HR], 1.002; 90% confidence interval [CI], 0.9–1.12). The median PFS was 13 months for patients in the TC group and 14 months for patients in the TAP group (HR, 1.032; 90% CI, 0.93–1.15).[13]

- These results led to the use of TC as the standard adjuvant treatment for patients with stages III and IV disease.

- The use of cisplatin and doxorubicin compared with whole-abdominal radiation therapy was studied in a trial of patients with stage III or IV disease with residual tumors smaller than 2 cm and no parenchymal organ involvement.[14][Level of evidence A1]

- Results suggest that cisplatin and doxorubicin improved OS, compared with whole-abdominal radiation therapy (adjusted HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.52–0.89; P = .02; 5-year survival rates of 55% for cisplatin and doxorubicin vs. 42% for whole-abdominal radiation).

- Several trials support combination chemotherapy for patients with stage III, stage IV, and recurrent carcinosarcoma.

- The GOG-108 trial of ifosfamide, with or without cisplatin, as first-line therapy in patients with measurable advanced or recurrent carcinosarcomas demonstrated a higher response rate (54% vs. 34%) and longer PFS in the combination arm (6 months vs. 4 months), but there was no significant improvement in survival (9 months vs. 8 months).[15][Level of evidence A1]

- The follow-up GOG-0161 study (NCT00003128) used 3-day ifosfamide regimens (instead of the more-toxic 5-day regimen in the preceding study) for the control and ifosfamide combined with paclitaxel (with G-CSF starting on day 4) for the study arm.[16]

- The combination regimen produced superior response rates (45% vs. 29%), PFS (8.4 months vs. 5.8 months), and OS (13.5 months vs. 8.4 months). The HR for death also favored the combination regimen (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.49–0.97).[16][Level of evidence A1]

- In this study, 52% of 179 evaluable patients had recurrent disease, 18% had stage III disease, and 30% had stage IV disease. In addition, there were imbalances between the treatment arms with respect to the sites of disease and the use of prior radiation therapy, and 30 patients were excluded for wrong pathology.

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy

Patients with inoperable disease caused by tumor that extends to the pelvic wall may be treated with a combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. The usual approach for radiation therapy is a combination of intracavitary and external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT).[17,18]

For patients with localized recurrences (pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes) or distant metastases in selected sites, radiation therapy may be an effective palliative therapy. Pelvic radiation therapy may be curative in pure vaginal recurrence when no previous radiation therapy has been used.

Hormone therapy

Progesterone and estrogen hormone receptors are commonly found in endometrial carcinoma tissues. Response to hormone therapy is correlated with the presence and level of hormone receptors and the degree of tumor differentiation.[19] Patients with tumors that are positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors respond best to progestin therapy.

When distant metastases, especially pulmonary metastases, are present, hormonal therapy is indicated. Patients who are not candidates for either surgery or radiation therapy may be treated with progestational agents, the most common hormonal treatment. Progestational agents produce good antitumor responses in 15% to 30% of patients. These responses are associated with significant improvement in survival.[19]

Standard progestational agents include:[19]

- Hydroxyprogesterone.

- Medroxyprogesterone.

- Megestrol.

Evidence (progestin therapy):

- One study followed 115 patients with advanced endometrial cancer treated with progestins.[20]

- Responses occurred in 75% of patients (42 of 56) with progesterone receptor–positive tumors.

- Responses occurred in 7% of patients (4 of 59) without detectable progesterone receptors.

A receptor-poor status may predict a poor response to progestins and a better response to cytotoxic chemotherapy.[21]

Other hormonal agents have shown benefit in treating endometrial cancer. Tamoxifen (20 mg bid) yields a 20% response rate in patients who do not respond to standard progesterone therapy.[22]

Aromatase inhibitors have also been evaluated for the treatment of advanced and recurrent endometrial cancer, although they yield lower response rates than progestational agents.[23]

Biological therapy

Several biological agents have been evaluated for the treatment of endometrial cancer.

- Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors.

Endometrial cancers often show alterations in the AKT-PI3K pathway, making mTOR inhibitors an attractive choice for clinical study in patients with metastatic or recurrent disease. Phase II studies of single-agent everolimus [24] and ridaforolimus [25,26] have predominantly shown disease stabilization. A phase II study of the combination of everolimus and letrozole showed a 32% response rate.[27][Level of evidence C3]

- Bevacizumab.

Immunotherapy

With the published results of The Cancer Genome Atlas, and as more is learned about the molecular drivers of endometrial cancer, the use of immunotherapy has been evaluated for the treatment of advanced and recurrent disease.

Evidence (immunotherapy):

- Study 309/KEYNOTE-775 (NCT03517449) was a large, international, multicenter, randomized trial that compared the combination of pembrolizumab (200mg intravenously [IV] every 3 weeks for up to 35 cycles) and lenvatinib (20mg orally daily) with physician's choice of chemotherapy. The study enrolled women with advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer who had disease progression after a platinum-based regimen (measurable disease was required). All histologies except carcinosarcoma and sarcoma were permitted. Patients were stratified by mismatch repair (MMR) status. The two primary end points were PFS and OS.[30]

- After a median follow-up of approximately 12 months in both groups, survivals were statistically longer for patients in the pembrolizumab-lenvatinib group. The benefit persisted despite the patients' MMR statuses. Among all patients, the median PFS was 7.3 months for patients who received pembrolizumab and lenvatinib and 3.8 months for patients who received chemotherapy (HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.48–0.66; P < .001). The median OS was 18.7 months for patients who received pembrolizumab and lenvatinib and 11.9 months for patients who received chemotherapy (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.55–0.77; P < .001).[30][Level of evidence A1]

- The most frequent serious side effect in the experimental group was hypertension.

- The double-blind placebo-controlled KEYNOTE-868 study (NCT03914612) included 810 patients with advanced (stage III, stage IVA, or stage IVB) or recurrent endometrial cancer.[31] Patients were randomly assigned to receive six cycles of paclitaxel and carboplatin with either pembrolizumab or placebo. Afterwards, patients received up to 14 cycles of maintenance therapy with pembrolizumab or placebo. Patients were stratified according to MMR statuses (proficient [pMMR; n =588] or deficient [dMMR; n = 222]) to investigate if the checkpoint inhibitor, pembrolizumab, was efficacious in patients with dMMR tumors.

- After a median follow-up of 12.0 months, the 1-year PFS for patients with dMMR tumors was 74% in the pembrolizumab group and 38% in the placebo group (HR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.19–0.48; P < .001).[31][Level of evidence B1]

- After a median follow-up of 7.9 months, the median PFS for patients with pMMR tumors was 13.1 months in the pembrolizumab group and 8.7 months in the placebo group (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.41–0.71; P < .001).[31][Level of evidence B1]

- Regardless of MMR status, pembrolizumab showed significant PFS improvement in patients with advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer.

- The phase III randomized KEYNOTE-B21 trial (NCT04634877) included 1,095 patients with newly diagnosed high-risk stage I to stage IVA endometrial cancer (including carcinosarcoma) without evidence of disease postsurgery. All patients received either six cycles of chemotherapy with optional EBRT or four cycles of chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation therapy. Vaginal brachytherapy was allowed in both groups. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either adjuvant pembrolizumab or placebo every 3 weeks for six cycles, then every 6 weeks for six cycles. A total of 66% of patients had stage III or stage IVA disease, 26% had dMMR tumors, and 67% were treated with radiation therapy.[32,33]

- After a median follow-up of 24 months, the 2-year disease-free survival (DFS) rate was 75% in the pembrolizumab group and 76% in the placebo group (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.79–1.32; P = .57).[33][Level of evidence B1]

- In the dMMR cohort, the 2-year DFS rate was 92.4% in the pembrolizumab group and 80.2% in the placebo group (HR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.14–0.69).

- No other predetermined subgroup benefitted from adding pembrolizumab.

This study evaluated giving pembrolizumab to patients with positive lymph nodes after surgery who had no other visible evidence of disease. It also evaluated combining radiation therapy and pembrolizumab. Results were significant because they expanded the population of patients who can receive pembrolizumab.

- The RUBY trial (NCT03981796) was a large multicenter trial in women with Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique stage III, IV, or recurrent endometrial cancer of all histologies not amenable to curative therapy. Unlike the Study 309/KEYNOTE-775 trial, some patients without measurable disease qualified for inclusion. Women were randomly assigned to receive TC with or without dostarlimab (500 mg IV) every 3 weeks for six cycles followed by maintenance dostarlimab (1,000 mg IV every 6 weeks) for up to 3 years. Patients were stratified by MMR status. The primary end point was PFS.[34]

- After a median follow-up of approximately 2 years, the dostarlimab group from the overall population had a 36% lower risk of progression or death (HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.51–0.80; P < .001). The dostarlimab group from the dMMR population had a 72% lower risk of progression or death (HR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.16–0.50; P < .001). Similar benefit was seen in OS (HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.46–0.87, P = .0021 for the overall population; HR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.13–0.70 for dMMR population).[34][Level of evidence B1]

These three studies demonstrate the activity and benefit of immunotherapy in the treatment of patients with advanced stage and recurrent endometrial cancer. These results may also facilitate the incorporation of such treatments into the up-front setting. More data are needed to help discern the role of immunotherapy in patients who historically would be managed with radiation therapy as part of the treatment plan.

Clinical trials

All patients with advanced disease should consider clinical trials that evaluate single-agent or combination therapy for this disease.

Studies of treatment failure patterns have found a high rate of distant metastases in the upper abdomen and in extra-abdominal sites.[35] For this reason, patients with stage III disease may be candidates for innovative clinical trials.

Treatment options under clinical evaluation for stage IV endometrial cancer include the following agents:

- Paclitaxel and carboplatin with or without metformin in stages III, IV, and recurrent endometrial cancer (GOG-0286B [NCT02065687]).

- PI3K/mTOR inhibitor in recurrent or persistent endometrial cancer (15-079 [NCT02549989]).

- Everolimus and letrozole or hormonal therapy in recurrent or persistent endometrial cancer (GOG-3007 [NCT02228681]).

- Everolimus, letrozole, and metformin in advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer (2012-0543 [NCT01797523]).

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Shih KK, Yun E, Gardner GJ, et al.: Surgical cytoreduction in stage IV endometrioid endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 122 (3): 608-11, 2011.

- Barlin JN, Puri I, Bristow RE: Cytoreductive surgery for advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol 118 (1): 14-8, 2010.

- Ball HG, Blessing JA, Lentz SS, et al.: A phase II trial of paclitaxel in patients with advanced or recurrent adenocarcinoma of the endometrium: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 62 (2): 278-81, 1996.

- Thigpen JT, Brady MF, Homesley HD, et al.: Phase III trial of doxorubicin with or without cisplatin in advanced endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 22 (19): 3902-8, 2004.

- Fleming GF, Brunetto VL, Cella D, et al.: Phase III trial of doxorubicin plus cisplatin with or without paclitaxel plus filgrastim in advanced endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 22 (11): 2159-66, 2004.

- Fleming GF, Filiaci VL, Bentley RC, et al.: Phase III randomized trial of doxorubicin + cisplatin versus doxorubicin + 24-h paclitaxel + filgrastim in endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Ann Oncol 15 (8): 1173-8, 2004.

- Arimoto T, Nakagawa S, Yasugi T, et al.: Treatment with paclitaxel plus carboplatin, alone or with irradiation, of advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 104 (1): 32-5, 2007.

- Sovak MA, Hensley ML, Dupont J, et al.: Paclitaxel and carboplatin in the adjuvant treatment of patients with high-risk stage III and IV endometrial cancer: a retrospective study. Gynecol Oncol 103 (2): 451-7, 2006.

- Hoskins PJ, Swenerton KD, Pike JA, et al.: Paclitaxel and carboplatin, alone or with irradiation, in advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol 19 (20): 4048-53, 2001.

- Pectasides D, Xiros N, Papaxoinis G, et al.: Carboplatin and paclitaxel in advanced or metastatic endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 109 (2): 250-4, 2008.

- Nomura H, Aoki D, Takahashi F, et al.: Randomized phase II study comparing docetaxel plus cisplatin, docetaxel plus carboplatin, and paclitaxel plus carboplatin in patients with advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma: a Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group study (JGOG2041). Ann Oncol 22 (3): 636-42, 2011.

- Dimopoulos MA, Papadimitriou CA, Georgoulias V, et al.: Paclitaxel and cisplatin in advanced or recurrent carcinoma of the endometrium: long-term results of a phase II multicenter study. Gynecol Oncol 78 (1): 52-7, 2000.

- Miller DS, Filiaci VL, Mannel RS, et al.: Carboplatin and Paclitaxel for Advanced Endometrial Cancer: Final Overall Survival and Adverse Event Analysis of a Phase III Trial (NRG Oncology/GOG0209). J Clin Oncol 38 (33): 3841-3850, 2020.

- Randall ME, Filiaci VL, Muss H, et al.: Randomized phase III trial of whole-abdominal irradiation versus doxorubicin and cisplatin chemotherapy in advanced endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 24 (1): 36-44, 2006.

- Sutton G, Brunetto VL, Kilgore L, et al.: A phase III trial of ifosfamide with or without cisplatin in carcinosarcoma of the uterus: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol 79 (2): 147-53, 2000.